The bulk of art history is a testament to what man makes of his experience in this strange mortal coil. But Main Street Art's current exhibit, "Trying to Understand the World," reveals two examples of the female gaze — one is a literal look at the sights of the city, and one is storytelling based in metaphor.

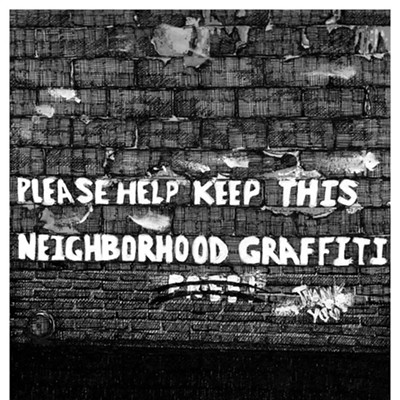

In her stark, highly detailed ink drawings, Brooklyn-based artist Anne Muntges recreates vignettes from her daily life in the city. She records specific street scenes and sights on subway cars, but also includes the thoughts of unknown others in the form of graffiti that seasons the surfaces.

"Drawing is my connection to the world," she says. "The series I am showing in this exhibition is an exploration of New York City, where I've drawn the marks that others have made."

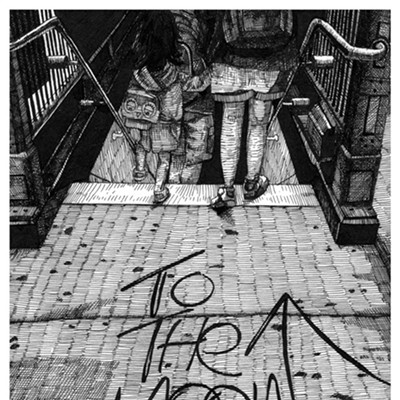

One drawing captures the backs of people descending into a subway entrance, with "TO THE MOON" hilariously scrawled on the ground, pointing into the abyss. Anyone who's been to Brooklyn in the past few years is familiar with this particular artist, who responded with delight when I tagged him in the photo of Muntges's drawing on Instagram.

Muntges's process involves walking through her neighborhood for four or five hours twice weekly, documenting hand marks through signage, graffiti, or accident along the way. "I am working to find my place in a new home through drawing," she says. "Something about the city has forced me to adapt to looking beyond the space I occupy to start to find how I fit into a greater whole."

With deft draftsmanship and careful consideration of the gritty textures of the city, Muntges's drawings are straightforward representations of what she's seen, but are peppered with plenty of cheek. In one work titled "Urinal Stance," Muntges saw something familiar in the bracing posture of the lower half of a man standing in a subway car, facing the doors impatiently.

A row of drawings includes written warnings: no sitting on this rather inviting stoop, don't put sneakers in the laundromat's dryers, and an angrily scrawled note on a destroyed machine after someone did try to dry rubber.

Other drawings record signs of the times: "We're f***ed" scribbled on the side of a phone booth, "F*** the Government" written on brick, appropriately directly above a heap of garbage. The central pole in a subway car blocks some letters on of a poster on the opposite wall, giving the illusion that it says "Cortesy Cunts." Kudos to the curators for hanging this drawing right next to another that contains a posted sign, "Aint Wet." You've gotta have fun in life.

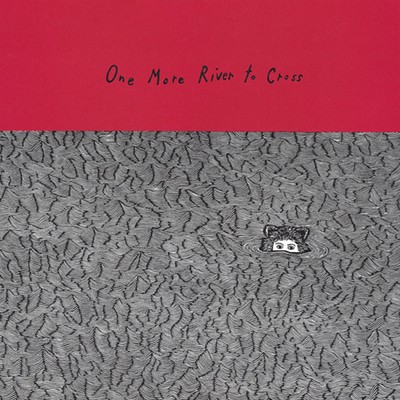

By contrast, Ithaca-based printmaker Sylvia Taylor's work is a dip into a slightly fantastical realm, in which various species interact in precarious ways and allude to a great impending heavy something.

"My relief prints are both playful and somber, with undercurrents of longing, vulnerability, and ambiguity," Taylor writes in her provided statement. "The images have a narrative quality, and are typically inhabited by animal characters that serve as a metaphor for the pathos and irony of the human condition."

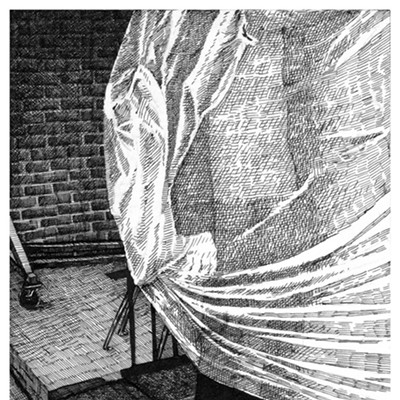

Taylor's print "Sheep Suit" shows an upright, human-shaped costume, ready for a human to don it and get fleeced, or a wolf to wear it and worry the flock. Though the simple shapes of the curling wool, ears, and hoofs are simply executed, her point is underscored by the passive slouch of the shoulders.

In "Escape Velocity," a peacock and a small mammal balance on a floating plank, apparently unconcerned with the sleuth of bears navigating dark waters below. The aptly-titled "Fugue" contains a similar split on the left, a sea of sheep's faces speaks of loss of identity, while on the right is a single shape in the form of a wishbone or dowsing rod.

While the walls in both rooms of the space offer the opportunity to look closely at the work of each artist, the second room is capped with a flurry of imagery by Taylor. A web of linen flags feature small prints of recurring animals, symbols, patterns, and architecture, suspended on crisscrossing lines in the installation "The Time Between the Dog and the Wolf." The work visually reads like a darker, more ominous version of Tibetan prayer flags, but perhaps telling the story of evolution in reverse.