In one respect, Tom Frey has been out of the public eye for decades. He left his last government position in December 1991, after failing to win a second term as Monroe County Executive. He’s been as active in public service since then as he was previously, but it has been in quieter efforts – important, but seldom publicized.

Today, Tom’s imprint is everywhere. And while cancer took his life on Saturday, his work will continue to enrich the community in an astonishingly broad number of areas.

MCC’s presence downtown. The art in the Rochester airport (what’s left of it). Motorists’ ability to turn right on red in New York State. Preservation of the photography collection at the George Eastman Museum. Curb cuts that make it easier for people with disabilities to cross the street. The county’s hazardous waste drop-off facility. A long walking-biking trail in the city’s northeast. The blue boxes for residential recycling. Preservation of houses and businesses in the city’s Swillburg neighborhood.

Tom Frey helped bring about all of that and a lot more during his time in government, in private law practice, and, in retirement, as a knowledgeable, well-connected community volunteer, advisor, and mentor. (A disclosure: Tom has been a personal friend and was the inspiration for my own early citizen activism in Rochester.)

His accomplishments all bear the stamp of deep ethical principles that seem to trace straight back to his upbringing in, as he put it, “a big Irish family.” He grew up in Corning, one of nine children, with parents who were devout Catholics and a father who was active in politics.

His accomplishments all bear the stamp of deep ethical principles that seem to trace straight back to his upbringing in, as he put it, “a big Irish family.” He grew up in Corning, one of nine children, with parents who were devout Catholics and a father who was active in politics.

Settling in Rochester after military service and college, he followed his father into politics, running first – unsuccessfully – for Rochester’s City Council, and then, in the early 1970’s, for Rochester school board. He went on to be a New York State Assembly member, director of operations under New York Governor Hugh Carey, general counsel to the state power authority, a member of the Board of Regents, and an attorney with Harris Beach. And in 1986 he re-entered politics, winning election as Monroe County Executive, the only Democrat to have held that office.

His has been a record of astonishing accomplishment, rooted both in his religious faith and in his almost fierce belief that government can do good – that it has a responsibility to help people, particularly the needy and the defenseless.

During his four years on the Rochester school board, he helped push an integration program, a predictably controversial plan that resulted in the defeat of pro-integration board members in a subsequent election and the reversal of the plan.

During his six years in the State Assembly, he chaired the transportation committee, leading to legislation permitting right turns on red lights and mandating curb cuts on new and reconstructed sidewalks.

And he got state legislation passed that kept the I-390 highway from barreling through southeast city neighborhoods. That capped efforts by neighborhood and environmental groups to block a push by business leaders, who wanted 390 to continue as a multi-lane highway on into the city, which would have destroyed a wide swath of homes and businesses along South Clinton Avenue.

The knowledge and experience Tom got from his work in the state has paid off for many Rochester-area organizations and institutions, including the George Eastman Museum. In 1984, the museum’s board of trustees, faced with a substantial cutback in Kodak funding and a critical need to properly house the museum’s valuable collection, voted to send the collection to the Smithsonian. That would have meant the death of the institution as an internationally important art museum, film repository, and research center. There would have been nothing here except George Eastman’s home, a monument to the founder of Eastman Kodak.

Museum supporters – in Rochester and around the country – responded with efforts to keep the archives here and build a new building, adequate for film preservation, research, and exhibitions. Key to pulling that off was getting financial support, and Tom played a critical role, getting a commitment from the New York State Assembly for $3 million for the building.

“If Tom Frey had not gotten involved,” says longtime friend and Eastman Museum supporter Tom Fink, “we would not have gotten the money, and we would not have gotten the building.”

Tom went after his most prominent elected position in 1986, running against County Executive Lucien Morin, who was popular but was saddled with charges of mediocre appointments and management.

Tom went after his most prominent elected position in 1986, running against County Executive Lucien Morin, who was popular but was saddled with charges of mediocre appointments and management.

Tom campaigned on the need for a more professional, less patronage-ridden county government. And those who worked with him in the county consistently mention his dedication to hiring talented people, whether they were Democrats or not.

“He liked to bring in highly motivated people,” says Brian Curran, who was deputy county executive. And, says Curran: “He had a strong commitment to equal opportunity and affirmative action. Given where we are today, in some ways some of the stuff seems almost quaint, but in the late 80’s…. I’m not sure the county had ever had a female department head. He made a real effort to diversify management operations.”

Reminiscing about his administration last December, Tom recalled the lack of racial diversity during the Morin administration. “When you went to a County Legislature meeting, there was a table where all the [administration] advisers sat, and I don’t remember there being a single minority.”

His insistence on diversity also encompassed the LGBTQ community. “It was a point of sensitivity he had,” says Brian Curran. “He made a real effort to push those values down through the administration.”

During the Frey administration’s four years, the county completed plans for an enlarged, modernized airport and got it built, despite airlines’ initial concerns about cost. And despite pushback from local conservatives, the new building included an impressive collection of works by Rochester artists (much of it removed under more conservative county administrations in 2006 and 2016).

Overcoming strong objections from the administration of Monroe Community College, Tom’s administration persuaded the college to create a campus in downtown Rochester to make it more accessible to city residents, particularly those depending on public transportation.

Facing a serious trash disposal problem as area landfills filled to capacity, the county initiated major waste reduction measures that continue today: distributing blue boxes to residents for recycling and creating a household hazardous waste facility where residents can drop off cans of unused paint, oil, pesticides, and similar materials.

And his administration was able to do what county government had struggled unsuccessfully to do for years: create a landfill in the Town of Riga, a feat that involved not only negotiating with the state for permits but also negotiating with the town, providing financial compensation in exchange for locating a controversial waste site there.

“When you think back,” says Brian Curran, “things like having a place to dump your garbage is kind of a given.” And so is recycling. And yet at the time, garbage was big news, with landfills exhausted, the need for additional disposal areas growing, and nobody wanting a landfill in their back yard.

To relieve serious overcrowding at the jail downtown, Tom’s administration pushed for two approaches: building a second facility, in Brighton near the MCC campus, and pushing hard for an alternatives to incarceration program, begun under Tom’s predecessor, Lou Morin.

Brian Curran describes the situation in the downtown jail before those initiatives: so overcrowded that prisoners were lying on mattresses on the floor, “packed in,” says Curran.

Tom, says Clay Osborne, who was Tom’s chief of operations, “believed that prisoners ought to be respected, treated well.”

The county made major improvements at Ontario Beach Park: a wider beach, a boardwalk, a bandstand, and renovations to the bathhouse.

Tom worked with local veterans to start planning the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Highland Park.

He pushed to have the county provide nurses in city schools, to expand health care for the poor, to improve the county’s social services department. His administration created dress and cab standards for airport taxis.

“What he accomplished in four years is totally mind-blowing,” says Bob Bonn, who was a senior staff assistant in the Frey administration.

Tom also raised taxes.

When he took office, the county’s financial situation was “horrible,” says Clay Osborne. The tax hikes got the county in better shape financially, but, says Osborne, “his reputation as a tax raiser didn’t help him when he had to run for re-election.” And in the 1991 election, Republicans ended the Frey administration’s short run.

Twenty-five years later, Tom seemed to have no regrets about the tax increases. “The fact is,” he said recently, “we’re not going to get anything done in this county, because we’re not going to be able to afford to – not unless we start building up a government that can handle the problems this [community] has.”

“We would be better off with a quarter percent increase in the state sales tax,” he said. “That would produce probably about $70 million a year and would go a long way toward getting the county so that it could do the programs it needs to do for people in need.”

“He’s the last county executive who actually wanted to do anything with county government,” says journalist Mark Hare. “What struck me most about him: he had a long career in public service, but he actually believed in public service.”

“He truly believed in government, that government can do good,” says Clay Osborne. “That was the general philosophy of his administration.”

Throughout his government service, he insisted on public input, believing that “you had to be willing to spend time listening to people talk about their concerns,” says Brian Curran. In public meetings, says Curran, “he would literally sit for three or four hours and listen to people.”

Curran recalls Tom telling him about his work for Governor Hugh Carey during the Love Canal environmental crisis in Niagara Falls. “He sat and listened to people for 8 or 10 hours,” Curran says. In a situation like Love Canal, “you had to at least pay people the respect of listening to them. If you were the person in charge, you had to be there.”

After retiring, Tom turned his attention to a wide variety of community activities, continuing his work in the fields he has been passionate about. He helped turn an unused rectory into a child-care center that serves poor children in the St. Michael’s neighborhood, a measure that not only provides an important service for poor families but has had the side benefit of providing financial support for the church itself.

He helped bring a lawsuit (unsuccessfully) against New York State, arguing that the state’s separation of school districts into individual city and suburban districts has led to economic and racial segregation that deprives city children of the sound, basic education mandated by the state constitution.

He worked with Bill Cala, former Fairport schools superintendent and a former interim superintendent in Rochester, to try to establish a school that would serve both city and suburban students. And he has provided advice and support for Great Schools for All, which hopes to get a countywide public magnet school created.

As with much of his other volunteer work, Tom has used his experience in government to help Great Schools, going to Albany with others to talk with representatives of the State Education department, putting the group in contact with Regents, helping the group understand how the State Education Department works.

He served on the board of the Genesee Land Trust. The organization had been focused on farmland and habitat protection in Monroe and Wayne Counties, but Tom convinced it to expand its scope to include natural areas in the city.

Among the results: The El Camino Trail – now renamed the Thomas R. Frey Trail at El Camino: a 2.25-mile pedestrian and bike trail in the city’s northeast, on what had been a CSX rail line.

Among the results: The El Camino Trail – now renamed the Thomas R. Frey Trail at El Camino: a 2.25-mile pedestrian and bike trail in the city’s northeast, on what had been a CSX rail line.

Reminiscing last December about the creation of the trail, Tom said he became aware of the abandoned rail bed and the little park that is now at its southern end during drives in the neighborhood with his daughter Sarah.

After services at nearby St. Michael’s Church, “Sarah and I got in the habit of driving over to St. Paul Boulevard,” Tom said. “We would drive six or seven blocks, and there was that nice little park. You didn’t see many people, but you also knew this was perfectly safe.”

And they saw the trail: “the perfect trail,” he said.

Tom, Jim Howe from the Nature Conservancy, and Gay Mills from the Genesee Land Trust began planning the trail that became, he said, one of the accomplishments he has been proudest of.

The accomplishment didn’t come easy. Tom met with city officials to interest them in the project, promoted it with the Genesee Transportation Council, reached out to members of Congress to help get the rights to the railway bed from CSX.

“There were times when we thought we might never get the trail,” says Gay Mills. But Tom “was persistent, enthusiastic, going in to see anybody and everybody.”

The result was the creation of the Corner Park at Conkey Avenue in 2008; a playground in 2009, the opening of the trail itself in 2012; and the formation of a landscape apprentice program, which teaches neighborhood young people about landscaping and conservation.

The trail provides a long, linear park in a dense urban neighborhood used by neighborhood and non-neighborhood residents. And it serves as the focal point of Conkey Cruisers, founded by registered nurse and neighborhood resident Theresa Bowick to promote an active, healthy lifestyle in her neighborhood. During the summer, Conkey Cruisers hosts bike rides on the El Camino Trail, provides bikes for cyclists needing them for the rides, and awards bikes to people who participate in 90 percent of the summer’s events.

Tom has provided support for programs that help the homeless, studied stained glass, led tours of St. Michael’s, been an active board member of the New York Civil Liberties Union, played euchre, encouraged young Democrats who are getting involved in politics. And at his wife Jacque Cady’s urging, he became a pretty accomplished zydeco dancer.

“He had all that energy,” Mark Hare said a few days before Tom’s death. “What strikes me now is that after all this time, there’s no ‘quit,’ no giving up: ‘Of course it can be done. You just have to find that path.’”

As word of Tom’s illness spread, tributes poured in from friends and people who had worked with him – many of them thanking him not only for his public service but also for his impact on them personally, for being a role model, an inspiration, a supporter when they needed help.

And many of them use the word “perseverance” when they talk about him. Long struggles and big setbacks didn’t deter him. The school integration plan he helped create may have been tossed out, but more than 45 years later, he was still pursuing its principle. And he didn’t regret his role in the controversial plan.

“It was still a model,” he said in December. “We have a district that has 90 percent free or reduced-lunch students” and are majority black and Hispanic, “and 18 other districts that are way majority white.”

All of the evidence, he said, is that students attending integrated schools do better.

“Politically,” he said, “it’s probably not wise to say so, but we should have one school district,” a metropolitan district that would eliminate the racial and economic isolation of the community’s students and the concentration of poverty in city schools.

A metro district is probably “politically impossible,” he agreed. “Maybe,” he said, “it’s time to bring another lawsuit.”

“Even as recently as a month ago,” says Mark Hare, “he was calling me asking if I thought there was any chance of another lawsuit. He’s still thinking: This can be done.”

Like many of us, Tom has believed that the divisions in the community – geographic, political – have kept us from achieving what we could achieve together. Talking with him a week before he died, I asked if he didn’t think that if he had run for county executive, say, 10 years ago, he might have been able to pull the community together.

“I’m not sure,” he said. “I would have just said some things that would have turned people off.”

Like what?

“You’ve got to raise taxes.”

Out of office, he kept his faith in the ability of government to do good. And despite the challenges and despite the ugliness of current politics, he continued to stay involved himself, helping others find ways to work with government to improve their community.

In a conversation a week before he died, I asked him why. “Somebody’s got to do it,” he said.

I asked whether he was optimistic.

“I don’t know if I’d use that word,” he said. “I just think you have to do it.”

Calling hours are today from 2 to 4 p.m. and again from 6 to 9 p.m. at Anthony Funeral Home, 2305 Monroe Avenue. A mass of Christian burial is tomorrow at 9:30 a.m. at St. Michael’s Church, 869 North Clinton Avenue, with interment at Mt. Hope Cemetery following the mass.

Today, Tom’s imprint is everywhere. And while cancer took his life on Saturday, his work will continue to enrich the community in an astonishingly broad number of areas.

MCC’s presence downtown. The art in the Rochester airport (what’s left of it). Motorists’ ability to turn right on red in New York State. Preservation of the photography collection at the George Eastman Museum. Curb cuts that make it easier for people with disabilities to cross the street. The county’s hazardous waste drop-off facility. A long walking-biking trail in the city’s northeast. The blue boxes for residential recycling. Preservation of houses and businesses in the city’s Swillburg neighborhood.

Tom Frey helped bring about all of that and a lot more during his time in government, in private law practice, and, in retirement, as a knowledgeable, well-connected community volunteer, advisor, and mentor. (A disclosure: Tom has been a personal friend and was the inspiration for my own early citizen activism in Rochester.)

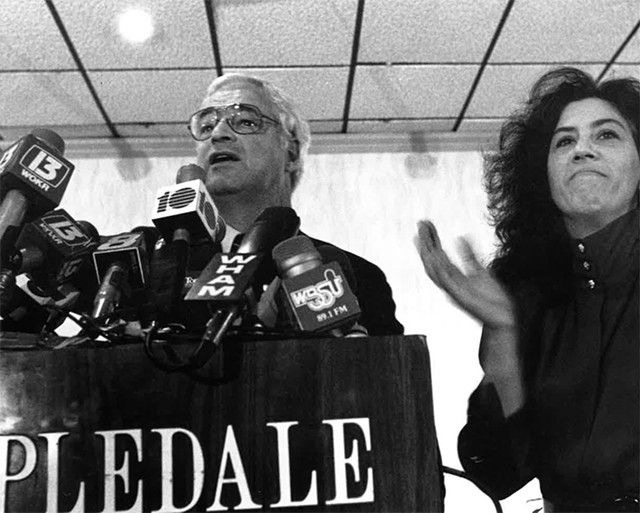

- PROVIDED PHOTO

- Tom Frey

Settling in Rochester after military service and college, he followed his father into politics, running first – unsuccessfully – for Rochester’s City Council, and then, in the early 1970’s, for Rochester school board. He went on to be a New York State Assembly member, director of operations under New York Governor Hugh Carey, general counsel to the state power authority, a member of the Board of Regents, and an attorney with Harris Beach. And in 1986 he re-entered politics, winning election as Monroe County Executive, the only Democrat to have held that office.

His has been a record of astonishing accomplishment, rooted both in his religious faith and in his almost fierce belief that government can do good – that it has a responsibility to help people, particularly the needy and the defenseless.

During his four years on the Rochester school board, he helped push an integration program, a predictably controversial plan that resulted in the defeat of pro-integration board members in a subsequent election and the reversal of the plan.

During his six years in the State Assembly, he chaired the transportation committee, leading to legislation permitting right turns on red lights and mandating curb cuts on new and reconstructed sidewalks.

And he got state legislation passed that kept the I-390 highway from barreling through southeast city neighborhoods. That capped efforts by neighborhood and environmental groups to block a push by business leaders, who wanted 390 to continue as a multi-lane highway on into the city, which would have destroyed a wide swath of homes and businesses along South Clinton Avenue.

The knowledge and experience Tom got from his work in the state has paid off for many Rochester-area organizations and institutions, including the George Eastman Museum. In 1984, the museum’s board of trustees, faced with a substantial cutback in Kodak funding and a critical need to properly house the museum’s valuable collection, voted to send the collection to the Smithsonian. That would have meant the death of the institution as an internationally important art museum, film repository, and research center. There would have been nothing here except George Eastman’s home, a monument to the founder of Eastman Kodak.

Museum supporters – in Rochester and around the country – responded with efforts to keep the archives here and build a new building, adequate for film preservation, research, and exhibitions. Key to pulling that off was getting financial support, and Tom played a critical role, getting a commitment from the New York State Assembly for $3 million for the building.

“If Tom Frey had not gotten involved,” says longtime friend and Eastman Museum supporter Tom Fink, “we would not have gotten the money, and we would not have gotten the building.”

- FILE PHOTO

- The caption: Frey and then-Democratic Party chair Fran Weisberg at the party celebrating Frey's election in 1986

Tom campaigned on the need for a more professional, less patronage-ridden county government. And those who worked with him in the county consistently mention his dedication to hiring talented people, whether they were Democrats or not.

“He liked to bring in highly motivated people,” says Brian Curran, who was deputy county executive. And, says Curran: “He had a strong commitment to equal opportunity and affirmative action. Given where we are today, in some ways some of the stuff seems almost quaint, but in the late 80’s…. I’m not sure the county had ever had a female department head. He made a real effort to diversify management operations.”

Reminiscing about his administration last December, Tom recalled the lack of racial diversity during the Morin administration. “When you went to a County Legislature meeting, there was a table where all the [administration] advisers sat, and I don’t remember there being a single minority.”

His insistence on diversity also encompassed the LGBTQ community. “It was a point of sensitivity he had,” says Brian Curran. “He made a real effort to push those values down through the administration.”

During the Frey administration’s four years, the county completed plans for an enlarged, modernized airport and got it built, despite airlines’ initial concerns about cost. And despite pushback from local conservatives, the new building included an impressive collection of works by Rochester artists (much of it removed under more conservative county administrations in 2006 and 2016).

Overcoming strong objections from the administration of Monroe Community College, Tom’s administration persuaded the college to create a campus in downtown Rochester to make it more accessible to city residents, particularly those depending on public transportation.

Facing a serious trash disposal problem as area landfills filled to capacity, the county initiated major waste reduction measures that continue today: distributing blue boxes to residents for recycling and creating a household hazardous waste facility where residents can drop off cans of unused paint, oil, pesticides, and similar materials.

And his administration was able to do what county government had struggled unsuccessfully to do for years: create a landfill in the Town of Riga, a feat that involved not only negotiating with the state for permits but also negotiating with the town, providing financial compensation in exchange for locating a controversial waste site there.

“When you think back,” says Brian Curran, “things like having a place to dump your garbage is kind of a given.” And so is recycling. And yet at the time, garbage was big news, with landfills exhausted, the need for additional disposal areas growing, and nobody wanting a landfill in their back yard.

To relieve serious overcrowding at the jail downtown, Tom’s administration pushed for two approaches: building a second facility, in Brighton near the MCC campus, and pushing hard for an alternatives to incarceration program, begun under Tom’s predecessor, Lou Morin.

Brian Curran describes the situation in the downtown jail before those initiatives: so overcrowded that prisoners were lying on mattresses on the floor, “packed in,” says Curran.

Tom, says Clay Osborne, who was Tom’s chief of operations, “believed that prisoners ought to be respected, treated well.”

The county made major improvements at Ontario Beach Park: a wider beach, a boardwalk, a bandstand, and renovations to the bathhouse.

Tom worked with local veterans to start planning the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Highland Park.

He pushed to have the county provide nurses in city schools, to expand health care for the poor, to improve the county’s social services department. His administration created dress and cab standards for airport taxis.

“What he accomplished in four years is totally mind-blowing,” says Bob Bonn, who was a senior staff assistant in the Frey administration.

Tom also raised taxes.

When he took office, the county’s financial situation was “horrible,” says Clay Osborne. The tax hikes got the county in better shape financially, but, says Osborne, “his reputation as a tax raiser didn’t help him when he had to run for re-election.” And in the 1991 election, Republicans ended the Frey administration’s short run.

Twenty-five years later, Tom seemed to have no regrets about the tax increases. “The fact is,” he said recently, “we’re not going to get anything done in this county, because we’re not going to be able to afford to – not unless we start building up a government that can handle the problems this [community] has.”

“We would be better off with a quarter percent increase in the state sales tax,” he said. “That would produce probably about $70 million a year and would go a long way toward getting the county so that it could do the programs it needs to do for people in need.”

“He’s the last county executive who actually wanted to do anything with county government,” says journalist Mark Hare. “What struck me most about him: he had a long career in public service, but he actually believed in public service.”

“He truly believed in government, that government can do good,” says Clay Osborne. “That was the general philosophy of his administration.”

Throughout his government service, he insisted on public input, believing that “you had to be willing to spend time listening to people talk about their concerns,” says Brian Curran. In public meetings, says Curran, “he would literally sit for three or four hours and listen to people.”

Curran recalls Tom telling him about his work for Governor Hugh Carey during the Love Canal environmental crisis in Niagara Falls. “He sat and listened to people for 8 or 10 hours,” Curran says. In a situation like Love Canal, “you had to at least pay people the respect of listening to them. If you were the person in charge, you had to be there.”

After retiring, Tom turned his attention to a wide variety of community activities, continuing his work in the fields he has been passionate about. He helped turn an unused rectory into a child-care center that serves poor children in the St. Michael’s neighborhood, a measure that not only provides an important service for poor families but has had the side benefit of providing financial support for the church itself.

He helped bring a lawsuit (unsuccessfully) against New York State, arguing that the state’s separation of school districts into individual city and suburban districts has led to economic and racial segregation that deprives city children of the sound, basic education mandated by the state constitution.

He worked with Bill Cala, former Fairport schools superintendent and a former interim superintendent in Rochester, to try to establish a school that would serve both city and suburban students. And he has provided advice and support for Great Schools for All, which hopes to get a countywide public magnet school created.

As with much of his other volunteer work, Tom has used his experience in government to help Great Schools, going to Albany with others to talk with representatives of the State Education department, putting the group in contact with Regents, helping the group understand how the State Education Department works.

He served on the board of the Genesee Land Trust. The organization had been focused on farmland and habitat protection in Monroe and Wayne Counties, but Tom convinced it to expand its scope to include natural areas in the city.

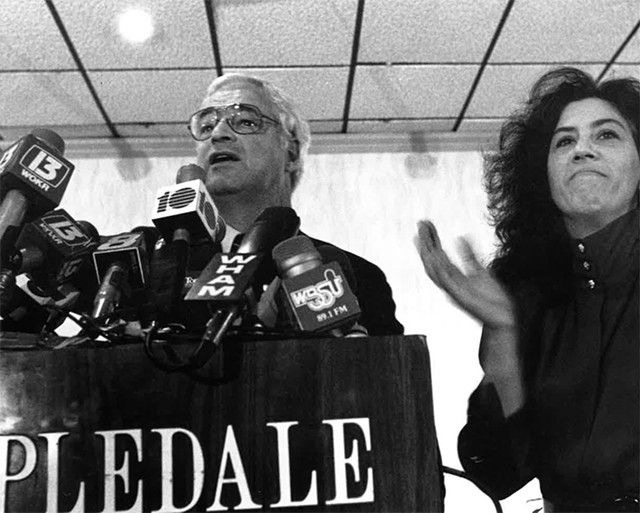

- PROVIDED PHOTO

- A runner crosses the finish line in a 5K run on El Camino Trail in the city's northeast.

Reminiscing last December about the creation of the trail, Tom said he became aware of the abandoned rail bed and the little park that is now at its southern end during drives in the neighborhood with his daughter Sarah.

After services at nearby St. Michael’s Church, “Sarah and I got in the habit of driving over to St. Paul Boulevard,” Tom said. “We would drive six or seven blocks, and there was that nice little park. You didn’t see many people, but you also knew this was perfectly safe.”

And they saw the trail: “the perfect trail,” he said.

Tom, Jim Howe from the Nature Conservancy, and Gay Mills from the Genesee Land Trust began planning the trail that became, he said, one of the accomplishments he has been proudest of.

The accomplishment didn’t come easy. Tom met with city officials to interest them in the project, promoted it with the Genesee Transportation Council, reached out to members of Congress to help get the rights to the railway bed from CSX.

“There were times when we thought we might never get the trail,” says Gay Mills. But Tom “was persistent, enthusiastic, going in to see anybody and everybody.”

The result was the creation of the Corner Park at Conkey Avenue in 2008; a playground in 2009, the opening of the trail itself in 2012; and the formation of a landscape apprentice program, which teaches neighborhood young people about landscaping and conservation.

The trail provides a long, linear park in a dense urban neighborhood used by neighborhood and non-neighborhood residents. And it serves as the focal point of Conkey Cruisers, founded by registered nurse and neighborhood resident Theresa Bowick to promote an active, healthy lifestyle in her neighborhood. During the summer, Conkey Cruisers hosts bike rides on the El Camino Trail, provides bikes for cyclists needing them for the rides, and awards bikes to people who participate in 90 percent of the summer’s events.

Tom has provided support for programs that help the homeless, studied stained glass, led tours of St. Michael’s, been an active board member of the New York Civil Liberties Union, played euchre, encouraged young Democrats who are getting involved in politics. And at his wife Jacque Cady’s urging, he became a pretty accomplished zydeco dancer.

“He had all that energy,” Mark Hare said a few days before Tom’s death. “What strikes me now is that after all this time, there’s no ‘quit,’ no giving up: ‘Of course it can be done. You just have to find that path.’”

As word of Tom’s illness spread, tributes poured in from friends and people who had worked with him – many of them thanking him not only for his public service but also for his impact on them personally, for being a role model, an inspiration, a supporter when they needed help.

And many of them use the word “perseverance” when they talk about him. Long struggles and big setbacks didn’t deter him. The school integration plan he helped create may have been tossed out, but more than 45 years later, he was still pursuing its principle. And he didn’t regret his role in the controversial plan.

“It was still a model,” he said in December. “We have a district that has 90 percent free or reduced-lunch students” and are majority black and Hispanic, “and 18 other districts that are way majority white.”

All of the evidence, he said, is that students attending integrated schools do better.

“Politically,” he said, “it’s probably not wise to say so, but we should have one school district,” a metropolitan district that would eliminate the racial and economic isolation of the community’s students and the concentration of poverty in city schools.

A metro district is probably “politically impossible,” he agreed. “Maybe,” he said, “it’s time to bring another lawsuit.”

“Even as recently as a month ago,” says Mark Hare, “he was calling me asking if I thought there was any chance of another lawsuit. He’s still thinking: This can be done.”

Like many of us, Tom has believed that the divisions in the community – geographic, political – have kept us from achieving what we could achieve together. Talking with him a week before he died, I asked if he didn’t think that if he had run for county executive, say, 10 years ago, he might have been able to pull the community together.

“I’m not sure,” he said. “I would have just said some things that would have turned people off.”

Like what?

“You’ve got to raise taxes.”

Out of office, he kept his faith in the ability of government to do good. And despite the challenges and despite the ugliness of current politics, he continued to stay involved himself, helping others find ways to work with government to improve their community.

In a conversation a week before he died, I asked him why. “Somebody’s got to do it,” he said.

I asked whether he was optimistic.

“I don’t know if I’d use that word,” he said. “I just think you have to do it.”

Calling hours are today from 2 to 4 p.m. and again from 6 to 9 p.m. at Anthony Funeral Home, 2305 Monroe Avenue. A mass of Christian burial is tomorrow at 9:30 a.m. at St. Michael’s Church, 869 North Clinton Avenue, with interment at Mt. Hope Cemetery following the mass.