Windsor Asamoah-Wade took to teaching immediately. He had a full schedule in the Rochester City School District and jumped at every opportunity to coach. He was visible in the neighborhood, too; his students often called out his name when they saw him walking his dog or riding his bike.

But Asamoah-Wade wasn't certain in those early years if teaching was the career he wanted; he wondered if a more lucrative field would be better in the long run.

But then something happened that changed his mind, he says.

"I moved from the school I was at to School Without Walls, and it was the end of the day when the office called me," he says. "They said, 'Mr. Wade, there's a whole bunch of kids here who asked to see you. You better come down here.'"

It was a group of 15 to 20 students from his former school.

"They said, 'Mr. Wade, why did you leave us?'" he says. "I didn't realize until then what I meant to the kids. That was my 'aha' moment and I never looked back."

He calls it the day that teaching chose him. Asamoah-Wade has been teaching in the Rochester school district for more than 30 years now, 27 of them at School Without Walls.

He says that the secret to being an effective teacher is to show students that you care about them.

"Some of them have even called me 'dad,'" he says. "Maybe it's because I talk to them the way I talked to my own children."

- PHOTO BY MARK CHAMBERLIN

- Windsor Asamoah-Wade has been teaching at School Without Walls for nearly 30 years.

Asamoah-Wade is one of a relatively small core of black teachers in Rochester city schools, where about 80 percent of the district's 28,000 students are black or Latino.

Many educators, especially those working in urban school districts, stress the importance of having teachers of color in the classroom. But the reasons vary and can be controversial.

Some say that it's simply a matter of diversity and that the teacher's race is irrelevant when it comes to achievement for students of color. Even many of the Rochester school district's former superintendents, including Manuel Rivera and Bolgen Vargas, said that a teacher's race doesn't determine whether that teacher will be effective.

Good teachers build relationships with their students and it grows from genuinely caring about them and wanting them to succeed in all areas of their lives, these educators say.

But other teachers, administrators, and school officials say that while that's true, it's also a politically correct response. To say otherwise would insult and alienate more than half of the city's teaching staff, they say.

Teachers of color can provide a distinct level of understanding and cultural competency that inspires black and brown students and boosts them socially and academically, they say.

And they say that the Rochester school district, like many mid-size and large urban school districts, is mired in institutional racism. They cite disproportionately high suspension rates for African-American students; extremely low graduation rates for same, particularly black boys; and security checkpoints inside schools that they say create a prison-like environment.

Some of the educators are convinced that if black teachers made up at least 45 to 50 percent of the workforce in city schools that test scores and graduation rates would go up dramatically. Attendance would be higher, too, and suspensions would be lower, they say.

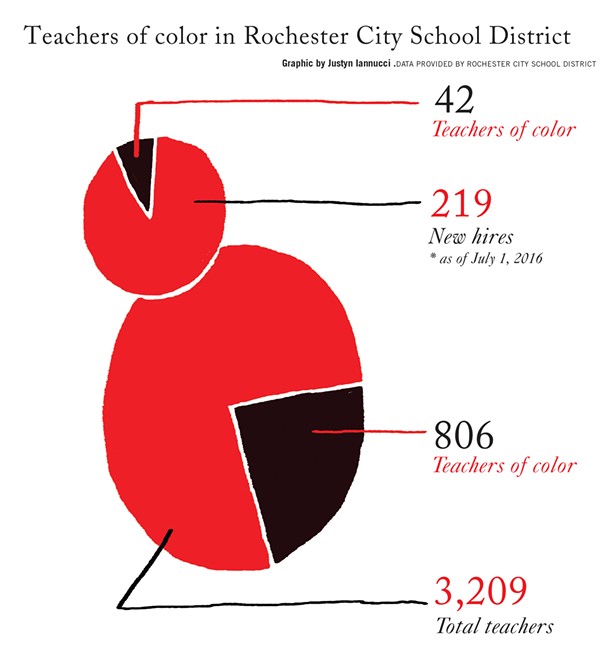

But the city school district is nowhere near that range. Out of a workforce of 3,209 teachers, 806 or 25 percent are teachers of color. And of the 219 new hires since July of this year, 42 or 19 percent are teachers of color.

Adam Urbanski, president of the Rochester Teachers Association, acknowledged the need for more teachers of color in an interview last year with the Minority Reporter.

"We recognize these mostly female, mostly middle class, mostly suburban teachers come here, and they are totally clueless as far as knowing anything about the students," he said.

The Rochester school district isn't unique. A major report from the Albert Shanker Institute released last year shows that gains in teacher diversity are modest in some urban school districts and that the ranks are declining in others, nationwide. Numerous explanations exist.

For example, while the report shows that teacher diversity grew during the 1980's and '90's, the minority student population grew at a much faster pace, particularly in urban school districts.

But more significant is the impact of reform measures. Even as minority children were integrated into largely white school systems under Brown v. Board of Education, minority teachers didn't always follow them. And more recent efforts to turn around or close low-performing schools have in many cases left fewer minority teachers in those school systems.

The Shanker Institute report, which was commissioned by the American Federation of Teachers, examined teacher diversity in nine cities: New York, Boston, Washington, Chicago, Cleveland, New Orleans, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and San Francisco.

The number of black teachers declined in all nine cities from 2002 to 2012. And even though there were some slight increases in the number of Latino teachers, the population of Latino students has increased nationwide, limiting a gain in representation, the report says.

Educators' views on teacher diversity are in some respects a microcosm of the general public's. There's even a wide spectrum of ideas among black teachers about its importance, why it's important, and how exactly it impacts all students, but especially students of color.

Asamoah-Wade views learning as a relationship-oriented process and puts less emphasis on a teacher's race.

"I don't know about this whole thing and whether the color of the teacher has an overwhelming influence on the performance behavior of a child," he says. "I had one black teacher from K through 12th grade. I can honestly say that one of the main reasons I even thought of becoming a teacher was from the examples I had from teachers who happened to be white. It was what they impressed upon me."

Asamoah-Wade grew up in rural Orleans County. His parents stressed the importance of education and taught him not to judge anyone based on race, ethnicity, or religion, he says.

"I was taught that the teacher has knowledge and training and wisdom that I should respect," he says. "My dad was a Teamster and my mom earned a bachelor's degree in nursing. They were part of the black migration North. They understood Jim Crow; they experienced it. They didn't want us to have the same educational restrictions that they did. We were expected to behave and to do the best work we could in school."

Donnell Johnson and Mark Morrison are African-American teachers with more than 20 years of experience. Their colleague, Dan Dunne, is white and is also a veteran teacher. The three men call themselves "Monrovians," since they all teach at Monroe High School.

They don't dismiss the value of teacher diversity, but say that other factors that influence student performance are just as important. And that includes teacher training, they say.

Few new teachers are fully prepared to walk into an urban school district and be effective, Johnson says.

"I realized I didn't have the skill set when I first started out," he says. "Many colleges and universities have a one-size-fits-all teacher preparation program, and they're not equipping new teachers entering the field for work in urban school districts."

Teamwork between teachers is essential to help make up for the lack of preparation, Johnson says. More experienced teachers need to guide new teachers who don't know the students, their home lives, their culture, or even when students are cursing at them in front the class, he says.

"You have to want to be here in this school," Dunne says. "Our kids have challenges, but our cultural diversity is a strength that suburban schools don't have."

The three are passionate about seeing Monroe removed from the state's list of receivership schools, which means that they are among the lowest performing in the state. And they say that Monroe is undergoing a transformation, which they credit to the school's new principal.

If relationship-building is a pillar of good teaching, then communication is critical, says Shaun Nelms, superintendent of East High School. It's important to understand that the way teachers communicate with students and vice-versa is shaded to some extent by past experiences, he says.

- PHOTO BY MARK CHAMBERLIN

- Shaun Nelms is superintendent of East High School.

"If I have received information that I have deemed or perceived to be racist, I'm much more likely to view other similar experiences through that same lens," Nelms says. "If you approach me based on past experiences, the way you treat me will be dictated accordingly. If being a 6'3" black male that weighs 250 pounds is from your experience intimidating, then you will approach me timidly."

Nelms says that he can't control that experience and that people should consider how black students feel. As children they become masters at code-switching: adjusting their behavior and demeanor depending on the social context, he says.

"We often view [black] students through the eyes of poverty and underappreciate some of their soft skills – the resilience and the ability to adjust to complex situations, code-switching, and being able to adapt," he says. "I would say that's a strength."

Focusing on whether white teachers are racist or whether they can teach black youth misses the point, Nelms says.

"The question is how we change the perspective of the adults in ways that allow them to view kids as individuals," he says. "And how do we help students understand that the adults they interact with are individuals, too, and not the same as the teacher they may have dealt with five years earlier – a teacher who may not have shown themselves to be culturally competent?"

It takes a lot of positive experiences to reset the mind after a negative one, Nelms says. Changing attitudes takes time, and understanding the insidious nature of racism is not the sole responsibility of teachers; children interact with lots of people with the wrong attitude, he says.

"Often the focus is on teachers because they interface with students and parents most, but within the school system there are many adults who control the first interaction with kids and parents that are not teachers," Nelms says.

That includes school security, bus drivers, and food servers, he says.

"There are so many other adults who are non-teaching staff that paint a picture of schooling for our kids that focusing on one subgroup becomes unfair," he says.

Nelms cringes when he hears people say that they want to hire black male teachers because they can better discipline black students, he says. A Washington Post article written by US Education Secretary John King earlier this year referred to this as the "invisible tax" on black male teachers.

That's just as racist as saying a black male isn't smart enough for the job, Nelms says.

"Black men are not given the respect as the intellectual leaders that they are and that they don't have more to offer than just being a social connection to the kids," he says. "Some of the most prominent educational leaders have been black men and they did it not by being physical, but by being smart men."

Brandon White and Banke Awopetu McCullough are younger black teachers and they take a strong stance on the need for more black teachers in Rochester.

They say that they often see white teachers treat white and black students differently.

- PHOTO BY MARK CHAMBERLIN

- Banke Awopetu McCullough, who last taught at All City High, told her students that being black is synonymous with excellence.

"I've encountered blatant racism to kids and I've encountered coded racism on an interpersonal level," says White, who teaches seventh and eighth grade in the Rochester school district.

He has seen children of color who misbehave receive harsher punishment than white kids who do essentially the same thing, he says. And white students frequently don't receive the same social-emotional diagnoses as black children when they have learning problems, White says.

There's a well-documented history of what experts refer to as "overprescribing" in schools with large numbers of minority children: disproportionate numbers of black and brown children are pipelined into special education programs and receive harsher punishment for misbehaving than white children.

White recalls a rambunctious white male student who exemplified this difference, he says.

"He was a good kid, a good spirit," he says. "But boys, we can be knuckleheaded. We can be easily distracted. He was just all boy. But I looked at him no differently than the other boys who had the same disposition. That couldn't have been said for one or two white teachers. If a black or brown kid did the same things as this white kid, there would have been consequences."

A recent Mother Jones article refers to a London School of Economics study that shows that white teachers grade black and Latino children more harshly for the same performance, accounting for as much as 22 percent of the achievement gap between white students and students of color.

A Vanderbilt University study shows that white students are roughly twice as likely to be placed on gifted tracks as black students, even when the test scores are comparable. But the advantage for white students fades when black students are evaluated by black educators, the study says.

And a recent study from Johns Hopkins University shows that black teachers are much more likely than white teachers to think that black students will complete high school and go on to earn a college degree, especially a black male student.

Awopetu McCullough last taught at All City High. She is resolute in her belief that the district needs more black teachers.

"Just seeing a person in the classroom that is the same race, culture, gender, or where you're from, that type of relatability allows you to dream for yourself," she says. "'This is what's possible.'"

But it goes beyond that, she says.

"I'm very explicit and unapologetic about what black students need, and they need black teachers who have a particular awareness about black history and intentionality about what they do," she says. "I believe black is synonymous with excellence. Anything short of that is unacceptable."

It's heartbreaking when she meets black students who have developed a negative self-image so early in life, but it's understandable, because the negative messaging, especially from news media, is all around them, she says.

"I've had kids tell me, 'Oh, come on, Miss, we black,'" she says. "I'll tell them, 'Exactly, which is why you're going to do it again and get it right this time. I have expectations of you because I know what you're capable of. Any teacher that's giving you easy work either thinks you're stupid or doesn't care about you.'"

McCullough has little tolerance for people who use language like "unrelenting poverty" when describing the lives of city students. It's a benevolent way of saying that society should have low expectations for them, she says.

You can't teach in the city school district and not talk about racism, she says; it's irresponsible.

"I could puke when any person tells me they're colorblind," she says. "You need to see a doctor about that because you do see color. Let's be serious."

Racism in the city school district isn't talked about because it makes people uncomfortable, says McCullough's former colleague, Brandon White.

"First, you have to agree that it's real and then you have to find ways to communicate it to a 5 year old who has to suffer through it," White says. "If 5 year olds are old enough to understand stranger danger, they're old enough to understand racism. It's an abstraction, but it happens just like child abduction."

Joy DeGruy, a nationally-known speaker, educator, and author, came to Rochester this summer to help teachers in the city school district have a long-overdue conversation about institutional racism in the schools, she says.

She doesn't mince words. Abysmally low graduation rates, especially for black males, and a bureaucracy that lacks accountability and is extremely resistant to change make the Rochester school district one of the worst she's seen, she says. She asks why more parents and community leaders aren't demanding change.

"It's horrific what's going on in Rochester, horrific," DeGruy says.

What's happening in Rochester is victim-blaming aimed at black and Latino students and their parents, she says.

"'They're just dysfunctional. They're poor. They're incapable of learning. It's the parents' fault. They're violent,' and on and on," DeGruy says.

DeGruy has held conversations and seminars with black parents across the US, and says that one finding stands out: Black children with mostly or all white teachers often come home and say that their teacher doesn't like them.

"That's not a normal thing for most children to say," she says. "And it doesn't matter whether it's perceived or real -- they don't feel liked. And here's the answer; often they aren't liked. Their teachers are afraid of them. Their teachers are impacted by implicit bias from media and from everything that gets promoted about children of color in this country. We want to believe that for some reason when we go into a classroom it all just floats away, and it doesn't. Our children can feel it."

DeGruy is convinced that increasing the number of teachers of color in the nation's classrooms will not only counter some of these attitudes and experiences, but will result in better test scores for students of color and go a long way to close the achievement gap between white students and students of color. Everything else has been tried, she says, including creating a parallel public education system with non-union charter schools. But little has changed, she says.

"There's this feeling of futility in school districts like Rochester because what we won't look at is the systemic problem of institutional racism," DeGruy says. "These systems are deeply entrenched, but if the keys to the kingdom are so strongly protected, nothing is going to change."

- PHOTO BY MARK CHAMBERLIN

- Howard Eagle is a retired teacher and longtime Rochestereducation activist.

Howard Eagle, a longtime education activist and former teacher, and Cynthia Elliott, vice president of the Rochester school board, are fiercely outspoken about the need for more black teachers in city schools, and have been for years. It's not that white teachers can't teach black children, or that most white teachers in the district are racist, they say.

But many white teachers and some black teachers, too, don't understand what slavery has done to generations of black families; they have a hard time appreciating the collateral damage caused by white supremacy and white privileges, they say.

"When you look through the history books in a classroom and almost all of the accomplishments are by white people and few by black people, there's a disconnect," Elliott says.

Eagle s says that educators must have a real conversation about racism.

"Many teachers feel they have a right not to talk about it, that they shouldn't be compelled to talk about it, but they should," he says.

- PHOTO BY MARK CHAMBERLIN

- Idonia Owens, principal at School Without Walls, says that more teachers of color are needed in the classroom.

Idonia Owens, principal at School Without Walls, says that white teachers need to do "the work" to understand the deeper issues faced by African-American children.

"They need to take a deep look into themselves and recognize the internalized racism, recognize the advantages, and recognize that there is something going on with these kids that they didn't ask for," she says. "I have to see that 6'2" black boy not as a criminal, but as a whole child that has experienced trauma, who can't walk down the street without being suspected of something terrible, who probably in his lifetime will be stopped by a police officer more than once for doing nothing."

Recognition is growing in the city school district of the need for more teachers of color. The district has a "grow your own" program for high school and college students interested in working in urban school districts — the hope is that they'll stay in Rochester — and it has a teacher career training program at East High School.

The district also partners with Uncommon Schools, a charter schools network, on a teaching fellow program where black and Latino college juniors teach in summer programs. The fellows may receive job offers in either the city schools or in the charter network before they complete their senior year.

- PHOTO BY MARK CHAMBERLIN

- Cynthia Elliott is vice president of the Rochester school board.

But there are obstacles to employing more teachers of color, says Harry Kennedy, the district's chief of human resources. A serious one is the union contract which says that the last teachers hired are the first to go in the event of layoffs. Also: convincing candidates from another state to uproot their families and come to Rochester is difficult, Kennedy says.

Still, the bar must be raised, says Elliott, the vice president of the school board. Some of the district's previous hires, white and black, haven't impressed her in terms of their understanding of the reality of teaching in an urban setting, she says.

"Just because you're certified doesn't mean you're qualified," she says. "And just because you're my skin folk doesn't mean you're kin folk."