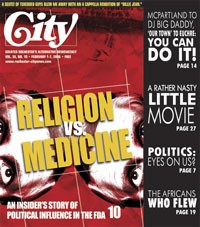

For 15 years, cell biologist Susan Wood worked as a Washington insider fighting for the inclusion of women in clinical trials, rallying the support of women in Congress, and tackling public policy obstacles. In 2000, she became the director of the Food and Drug Administration's Office of Women's Health --- a prestigious post from which she both educated health professionals about FDA decisions and defended itspolicies. But Wood's professional ascent came to a halt last August. When the FDA refused to switch the emergency contraceptive known as Plan B from a prescription drug to an over-the-counter drug, Wood resigned.

"I could no longer do my job properly," Wood said in an interview with City Newspaper recently. The FDA's decision, she said, will likely affect thousands of women who face the possibility of unwanted pregnancies every year --- including victims of incest and rape. The Association for Reproductive Health Professionals estimates that 48 percent of all pregnancies in the US are unintended. Plan B, a synthetic form of the hormone progesterone, is almost 90 percent effective in preventing pregnancy if taken within 72 hours of unprotected sex.

With her DC career finished, Wood has taken her story to the streets, traveling across the country. She was in Rochester last month, speaking at an event commemorating the 33rd anniversary of Roe v. Wade; the evening was sponsored by the National Organization of Women and Planned Parenthood.

- Frank De Blase

- Former Food and Drug Administration official Susan Wood: The FDA seems to have lost its independence.

When Plan B was approved as a prescription drug in 1999, the FDA had determined that it was safe and effective for all women of childbearing age. On this, there is little dispute. But in a series of moves that the Government Accountability Office has deemed "unusual," the FDA repeatedly stalled efforts to make Plan B available over-the-counter.

Pharmaceutical companies applying for a change from prescription to over-the-counter status must prove two things, says Wood: that users will know when to take the drug without medical advice, and that the product label is clear and easy to follow. In December 2003, an independent advisory committee charged with reviewing Plan B voted 23 to four in favor of approving the drug for over-the-counter use. While not binding on the FDA, committee recommendations typically mean that a product is headed toward approval, Wood says.

But then Dr. David Hager, a conservative Christian doctor on the advisory committee, wrote a letter to the FDA commissioner urging that the FDA assess whether younger teens are mature enough to use Plan B without a prescription. What was behind Hager's action isn't clear. According to media reports, Hager initially said that an unnamed FDA staffer requested that he draft a "minority report." But in subsequent interviews, Hager said the request came from outside the agency.

Although Wood is reluctant to talk about Hager's role regarding Plan B, much media attention has focused on the evangelist doctor turned public policy leader. Hager has said that his primary concern about making Plan B an over-the-counter drug is that it would promote teenage promiscuity. "I was concerned about 10, 11, 12-year old girls buying this product," Hager said in a November interview with CBS. "I'm not in favor of promotion of a product that would increase sexual activity among teenagers."

Wood says medical experts determined that Plan B does not alter sexual behavior among teens or adults. She adds that few doubt the drug's safety for women, young or old. The joint committee, she says, "had a unanimous vote that it was safe. Even Hager voted that it would be safe in an over-the-counter setting." A 2003 Nation article quoted Dr. Julie Johnson, a professor at the University of Florida's Colleges of Pharmacy and Medicine, as saying that in her four years on the committee, Plan B was "the safest product that we have seen brought before us."

But Hager has maintained that his reasoning is grounded in science. During a widely publicized 2004 speech at a Christian college in Kentucky, Hager said this about his opposition to Plan B: "I argued from a scientific perspective. And God took that information, and he used it through this minority report to influence a decision. You don't have to wave your Bible to have an effect as a Christian in the public arena."

Hager also charges that Plan B may cause an abortion. He notes that in certain instances Plan B can prevent a fertilized egg from implanting in the uterine wall. While the majority of health experts --- including the FDA, National Institutes of Health, and the AmericanCollege of Obstetricians and Gynecologists --- define pregnancy as occurring after implantation, a process which takes five to seven days, anti-abortion activists such as Hager disagree. "One of the mechanisms of action can be to inhibit implantation, which means that it may act as an abortifacient," Hager said in the CBS interview.

That view, says Wood, is fundamentally misguided. Even though Plan B is taken after sexual intercourse, its actions typically mimic those of conventional birth-control pills, she says. In rare cases when the drug prevents a fertilized egg from lodging in the womb, it is mimicking another popular contraceptive method: the intrauterine device, or IUD, she says.

Wood compares Plan B to breastfeeding, which also changes a woman's hormonal balance. "If you are breastfeeding, you are less likely to get pregnant," she says, and that's because you have this elevated progesterone level in your body, which is exactly what happens when you have Plan B emergency contraception."

"Anyone who is opposed to this really needs to be asked: are they also opposed to other forms of contraception?" says Wood. "If they are not opposed to regular birth-control pills but are opposed to emergency contraception, that's a contradiction."

In a seeming compromise, in May 2004the FDA mandated that Plan B's manufacturer, Barr Pharmaceuticals, come back with a proposal specifically addressing the needs of younger teens. A few months later, the company again applied for a status switch, limiting over-the-counter use of Plan B to those 17 and older.

But on August 26, 2005 --- incidentally, also Women's Equality Day --- the FDA determined that dual status for the drug would be too hard to enforce without a federal regulation. Drafting a regulation can take years, if not decades, to implement.

"I knew, as someone who's been in government for a long time, that when they say they're putting it into rulemaking, we're putting it in a black hole," says Wood. She adds that dual status exists for other drugs, including the nicotine patch, which can be bought without a prescription only by people 18 and older.

Outraged, Wood quit her job, saying that the FDA had let politics trump science."As soon as they made that announcement," she says, "it was very clear that both the process had been overruled [and] the science and the medical evidence had been overruled. Women's health and the public health were not the priority here."

Wood agrees that it makes sense to make sure younger teens know how and when to use Plan B. But, she says, it is imperative that the FDA adhere to the same standards for reproductive drugs as it does for other drugs. That criterion, she says, was not met.

Echoing Hager's minority report, Plan B critics in the FDA said too few young teenagers had been studied to insure that they would know how to use the drug. "And you might say: 'We should ask about that. That's a good question. We should have more data on these very young teens,'" says Wood. "Except for the fact that we have never asked that question before for any over-the-counter product. We never asked it about pain medication, things for menstrual cramps, migraines; we never asked it for antihistamines, cough medicines, cold medicines."

Wood says she is hesitant to blame any one person for Plan B's fate. She would, however, like to see Congress investigate what happened.

"The FDA seems to have lost its independence," she says. "This came from the commissioner's office in terms of the announcement, but the one statement I make on this is: I don't believe the agency was acting independently. The agency in the past has not lost its independence quite so clearly."

Much of Wood's suspicion stems from how decisions about Plan B were handled. Typically, lower-level directors determine whether a drug is suitable for over-the-counter use. For Plan B, several key players had determined that OTC status was appropriate. But in May 2004, Steven Galson, the director for the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research --- the FDA branch responsible for reviewing the drug --- wrote a letter saying that Plan B would not be approved for all women of childbearing age. The drug's manufacturers, he wrote, had to address the health needs of younger teens.

The FDA admits that Galson is not typically responsible for issuing such decisions. Its website reads: "Dr. Galson does not usually sign regulatory action letters. However, his opinion of the adequacy of the data in young adolescents differed from that of the review staff. He believes that additional data are needed."

Wood also questions the advisory-committee selection process. While committee members are typically chosen by lower FDA personnel and approved by the commissioner --- a White House appointee requiring Senate approval --- he and his superiors have the authority to appoint their own members. Wood says that's exactly what happened with Hager. In 2001, she says, "the center put forward a slate of people and they were signed off, on but a few people were added, including Dr. David Hager."

Wood paints a bleak picture for the future. The FDA's decision regarding Plan B undermines both science and good governance, she says. And she believes a shadow has been cast over the FDA and all impartial government agencies.

"This is connected clearly to contraception and family planning and things like that," she says, "but it's also connected to the larger issues of how an agency that we count on so much is not making its decisions based on the evidence. We and the health professionals should be able to count on FDA, as well as other agencies, for factual information. People shouldn't have to sit there and worry: 'Is this information that's coming to me no longer based on the facts?'"

Perhaps most disturbing is Wood's concern that other drugs might get mired in the abstinence debate. For example, FDA officials are currently reviewing a vaccine to prevent the human papilloma virus, which is mainly spread through sexual contact. "This virus is linked very strongly to causing cervical cancer," Wood says. "There are two vaccines now pending before the agency. I can't say that I think anything funny is going to go on at the agency, but then again I can't assure you that it won't. These same people who are opposed to emergency contraception have also started to lay the groundwork for being opposed to the human papilloma virus vaccine."

If it's approved, says Wood, the vaccine would be administered at around age 11 or 12 when children receive other immunizations. But social conservatives, she says, "don't want it to be widely available and routinely given because it might counter the abstinence message."

And, she adds: "I just ask the question: If they're raising concerns about emergency contraception, and the same concerns get raised astoundingly about a vaccine that can prevent cervical cancer, what will happen if and when there's ever an AIDS vaccine?"