Two current exhibits at George Eastman House, held in conjunction, explore the history of imaging innovations from Kodak's early days up through the present, and show an artistic documentation of the end of film manufacturing. Together, these exhibits provide a full picture of the imaging history of Image City, Rochester's hand in the development of digital technology, and how each shaped and changed our city's industry.

Canadian photographer Robert Burley's "The Disappearance of Darkness" feels like a proper elegy to an era, with eerie shots of stark and dated, abandoned manufacturing interiors, ghost offices, and modern ruins of warehouses and factories. Since the mid-2000's, Burley has documented the slow death of film manufacturing, capturing what remains and what is doomed: yawning cave-like spaces, manufacturing minutiae, and the implosions of iconic structures which provided the livelihoods for generations of Rochesterians and Kodak, Agfa, and Ilford employees in other countries.

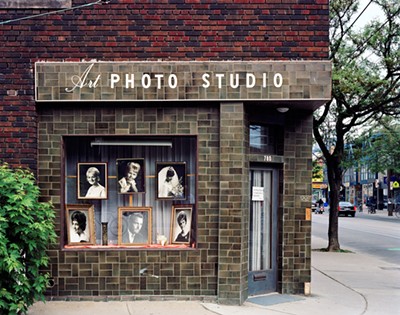

But subtle, related images are included, too. The 2005 image "Art Photo Studio: Closed Due to Retirement, Toronto, Ontario," marks the near obsolescence of certain traditional photographic industries at the commercial digital camera boom. A portrait of Rochester photographer Nathan Lyons' darkroom hints that the disappearance of darkness is not complete. An iPhone under glass scrolls through the 19 images captured by someone attending a 2009 rave at the single remaining building of a Kodak factory before the police stopped the party. The dim images, which give a vague sense of the 500 people who lit the darkened space with flashlights and digital cameras, were posted to Facebook.

Burley is mostly interested in our relationship with photography, and how that reflect on our relationship with the world. This is summed up in a particularly poignant image of the implosions of Buildings 65 and 69 at Kodak Park in 2007, at which Burley saw many other photographers there to document the event. In Burley's image, he has captured a man who has turned from the event, before the billowing dust cloud has settled, in order to check his image in the viewfinder of this camera. CITY's interview with Robert Burley can be found here.

"Innovation in the Imaging Capital" flexes some serious museum muscle, providing a fascinating and nuanced lesson on the history of imaging technology in Rochester, and its ongoing impact throughout the world. I was guided through the exhibit by Kathy Connor, curator of the George Eastman Legacy Collection, and Todd Gustavson, Curator of Technology, each of whom enthusiastically provided encyclopedic knowledge on the displayed items, which are drawn from the collections of Eastman House, Bausch & Lomb, Exelis, and others.

There is plenty to marvel over, from the early photo-duplication machine — a wooden counterpart to the modern Xerox copy machine mirroring it — to the 1967 Lunar Orbiter, with the capacity to develop film onboard; to the links between Kodak and modern medical imaging; to The Phantom 2 with Hero 3 camera — a drone — and the accompanying aerial video of the Eastman House grounds.

The show is a rare opportunity to showcase the physical relics of technologies that originated in Rochester industries, many of which are still impacting our lives. It also provides a chance to clear the air about a common misconception regarding Kodak. We often think and speak about the company's downfall as being driven by the end of film manufacturing, caused by the onset of digital technology, which is usually framed as having emerged out of left field. But as the show illustrates, the origins of digital imaging are within Kodak's own history. Kodak electrical engineer Steven Sasson produced the world's first digital camera in the 1970's — the toaster-sized bulk of which is displayed next to and contrasted with a sleek Samsung Galaxy S5 smartphone.

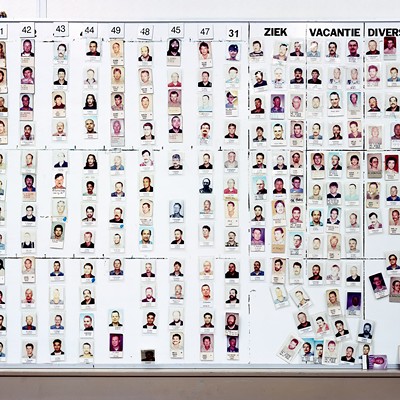

Through the 1980's, Kodak developed digital single-lens reflex (DSLR) cameras first for the U.S. government, then in small quantities for the professional photographer market, which were used mostly by the press. The early ones had sizable external batteries and memory storage.

"Innovation" contains dozens of important objects, mostly displayed in chronological order, categorized under five basic themes. A section on "Optics" explores the early partnership between Bausch & Lomb and Kodak, and includes samples of B&L eyeglasses, a folding student microscope, and a small section of a large lens that would be used for a space telescope.

The section "Capture, Save, and Share" provides a look at the evolution of the snapshot camera, from "The Kodak," to "The Brownie" — which sold for $1 (a roll of film cost 15 cents, and processing was 40 cents), putting photography in the hands of more people than ever — to the 1938 SuperKodak 620, which was the first auto-exposure camera; to The KodaChrome, with the first multilayer roll film; to the Instamatic, which simplified the loading of film.

"In my opinion, film is the most complicated consumer product that's ever been manufactured," Gustavson says. "We look at these tiny yellow boxes; it makes it look very simple. There's a lot of very expensive technology hidden in there. The company, these days, can coat up to 24 layers simultaneously when they put down the emulsion, but it's more than that. It's developing the specific chemicals and compounds that go into doing this. If you look at Kodak Park, in reality, what's included in that little yellow box is in fact all of Kodak Park." A fascinating scale model of the process of film coating is included next to an aerial shot of the Kodak Park buildings which house the massive apparatuses.

Located in a side gallery, "Photo in Flux" is a small, collaborative space for conversation about the state of photography today, offering the opportunity to provide feedback physically in the gallery or by posting online. You can join the conversation, by sharing your thoughts and insights about the state of photography, through text, images, and video posted on this site and in the special exhibition galleries through January 4.