Glenn McClure recently traveled to Antarctica to study changes in the ice. He'll use the data in a new musical project, the latest in McClure's history of combining math, music, and nature

For composers like Glenn McClure, there are sounds with melodious potential everywhere. Traffic, bread popping up out of a toaster, weather, glaciers, and so on; the opportunities are all around.

McClure recently returned from a 40-day excursion to Antarctica where he joined up with a team of scientists measuring the movement and sounds emitting from the Ross Ice Shelf — the continent's largest ice shelf. Always attentive, McClure picked up on additional surrounding sounds. He was in awe.

"Some of the sounds that I heard down there were surprising," McClure says. When discussing the science behind his art, McClure speaks in excited tones, and his eyes give way to a boundless curiosity — all beneath a composer's carefree coif.

"Natural sound was everywhere. In walking on the snow, it is so dry there — it's actually one of the driest places on the planet — it's so loud you can't have a stroll and a conversation with someone. The crunching snow makes too much noise. When I was out in the field recording the sound of Weddell seals and Adelie penguins, the sounds those animals were making were so surprising and so astonishing."

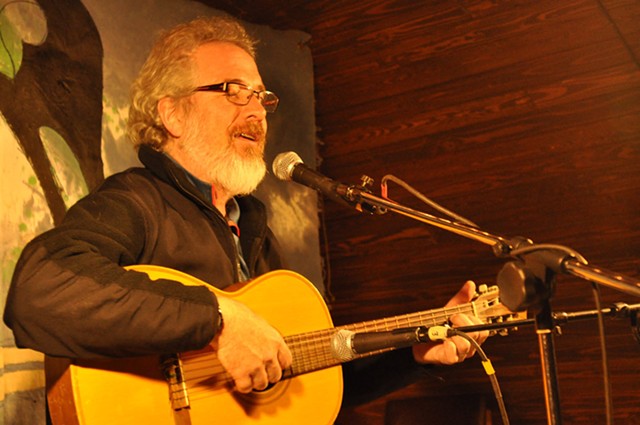

- PROVIDED PHOTOs

- A scientist, musician, and professor, Glenn McClure recently traveled to Antarctica as part of the National Science Foundation's Artists and Writers Fellowship.

McClure — an adjunct professor of English at SUNY Geneseo and an instructor of Chorale Arranging at The Eastman School of Music — was there to ultimately take the data retrieved on the ice shelf and use it in a composition using mathematics, music, and something referred to as sonification.

"Sonification is taking something that doesn't make sound and expressing it with sound," McClure says. Frequently, the sound is discovered or exemplified through numbers, not just notes. Yet it's the marriage of both numbers and notes that allow composers to construct pieces of music, giving their sources a voice.

According to McClure, music and numbers are one and the same; the world strikes a harmonious chord when they're aligned. The marriage of science and music is something that has been part of McClure's life since childhood, when a series of seizures and inner ear infections rendered him virtually speechless.

"From the time that I started speaking, I was a severe stutterer," McClure says. "What was clear from the beginning was that while my disability was severe, the only time I could open my mouth and not have that disability was when I sang because singing circumnavigates the disability in a person's brain. So music and singing became very important to me as a child. It was the only time I felt powerful and beautiful."

When he was 11 years old, McClure attended an intensive six-week, "almost boot camp-like" clinic at SUNY Geneseo.

"I learned a skill there that I use right now as I speak," he says. "It's a pretty intensive, intentional control of every muscle that makes me sound more or less like people who are normally fluent. My speech is actually better than normally fluent speech. But I can't really do it more than a couple hours at a time."

Music freed him. It's not something the composer has forgotten as he sets out to explore and rekindle the bond between music and mathematics. McClure takes data, frequently gathered from things found in nature, and transubstantiates it into melody and music — in a way personifying the data, animating it, and giving it life. And it's through this sonification that the man is re-introducing numbers and notes.

"This kind of composition work I'm doing is putting those things back together again," McClure says. "The ancient Greeks, all the way up to people like Galileo in the Renaissance, they saw music and mathematics and astronomy as all parts of — or different expressions of — a greater body of knowledge."

It was around the Renaissance that, McClure says, we started dividing up the disciplines, adding increased specialization in the things that we study, which led to narrower definitions of the words across the ages.

"Numbers alone equals arithmetic," he says. "Numbers in space equals geometry. Numbers in time equals music. And numbers in space and time equals astronomy."

- PROVIDED PHOTOs

- A scientist, musician, and professor, Glenn McClure recently traveled to Antarctica as part of the National Science Foundation's Artists and Writers Fellowship.

But you've got to wonder which side of the equation he's on. Is the man a scientist or a musician?

"Very much a musician," McClure says. "I'm a pretty lousy scientist, actually. I'm a much better musician. While the connection between music and my stuttering has been a part of my life forever, taking it a step further and actually going into the science of it and to do more work with scientists is something much more recent in my music making."

In his work entitled "Galileo's Universe," McClure took some of Galileo's data regarding movement of the planets, along with other related data sets collected by other scientists from the same period in time or in the same tradition, and transformed it into sound.

"Certainly among contemporary composers there's a whole range of different strategies," McClure says. "Many of them do a very rigid translation of a list of numbers into frequencies which creates some very interesting sounds. Those pieces don't often have a wide audience appeal to them because it's more of an aesthetic exploration, so to speak."

The other end of sonification is where composers respond personally and emotionally to, for example, a piece of nature, like the composer Bedrich Smetana's work "The Moldau."

"'The Moldau' is this beautiful musical picture of a river starting at its inception and ending in this great crescendo," McClure says. "What I'm interested in though, is splitting the difference between those two extremes, so I'm using some mathematical translation of data to create the core content of that data, the melodies and the harmonies, and then I take that core concept and put it in a larger arrangement that can have a broader audience."

McClure says his sonification, unlike Smetana's, isn't to be taken as literally.

"Not in the way I'm doing it," he says. "If you have something in nature that makes a sound, a composer can write music that imitates that sound. What I'm doing is a slightly different process, where that river is studied by a scientist and they've studied the velocity of the waves, they've measured the depth of the river at that point, and describe the river in numbers. I go back into those numbers, and then translate that into sound. In modular mathematics, somebody gives you a data set, a bunch of numbers and you find the range of that from the highest number to the lowest number. And then you divide up that range in a certain number of equal modules."

In other words: creating a scale.

"So if I translate a data set about the population of penguins in Antarctica, I could divide up those numbers into mod seven — do-re-mi-fa-so-la-ti — creating seven intervals. When I go back to these numbers I can plot them. And so once those data numbers are plotted on this chart of mod seven, you go back and put the notes on the page in the order that they were in in the data. And now, all of a sudden, the musical content is actually being driven by the numbers."

- PROVIDED PHOTOs

- A scientist, musician, and professor, Glenn McClure recently traveled to Antarctica as part of the National Science Foundation's Artists and Writers Fellowship.

McClure describes another approach: randomness. Here the music is generated by something else, with varying degrees of palatability and success.

"Sometimes it's going to sound beautiful," he says. "Sometimes it's not. Once you've generated that initial content, a composer has to come in and say, 'What can I do with this? Is this going to work as a melody? Is it going to work as a chord progression? If not, maybe it's going to work as a chord cluster that could decorate another part of the piece.' So it's partially this scientific translation of numbers to music. It's also very much the work of the composer who takes raw material and makes music with it."

McClure's passion, and his drive to get paid for it, led him to Antarctica.

"As a working composer," he says, "Part of my job is actually finding ways to get paid as an artist, so I'm frequently searching for funding or grant opportunities to do things. I stumbled upon this fellowship the National Science Foundation has called the Artists and Writers Fellowship. And what it is designed to do is to pair working artists in any discipline with scientists in the field to work side by side with them, live with them, learn everything they're doing in the field, and then come back and create artworks that tell their story. And also, in this case, tell the broader story of Antarctica."

This 40-day excursion was a teaching endeavor as well with several high schools and colleges partnering up with McClure for his adventure. That involved some Skype conversations between students in the States and McClure on the Ross Ice Shelf, which is several hundred meters thick and about the size of France.

- PROVIDED PHOTOs

- A scientist, musician, and professor, Glenn McClure recently traveled to Antarctica as part of the National Science Foundation's Artists and Writers Fellowship.

"It floats on the water; there is no land underneath it," McClure says. "Because of that, the ice shelf is subject to the movement of that water underneath it. So when pressure comes in through the water in the form of energy waves — infragravity waves they call them — from other parts of the planet, if there's excess pressure under there, that's going to heave up that whole ice shelf. And even though it's the size of France, it's going to affect that ice shelf. So when there are huge, big ripples in the water that's actually going to send a ripple through the ice shelf. The more volatile these infragravity waves are, the more cracking and breaking the ice shelf exhibits."

The specific scientific team McClure was working with was headed up by Peter Bromirski, a scientist from the University of California, San Diego. Bromirski's team has been using seismometers — typically used to measure earthquakes — imbedded in the Ross Ice Shelf for two years in order to measure the movement of the shelf based on interactions related to global warming. Part of their research is to find that connection while McClure collects data to interpret the whole affair musically ... perhaps just in time.

"Global warming has called us all together to be a part of the solution," he says. "In a specific way, it's too hard to tell. But in a broader sense, I think science is speaking to us in an increasingly urgent way."

With the gathering of data by the scientists complete, it's now left up to the composer, who is anxious to hear what it will become.

"The first job of a creator is to be a listener," he says. "The second job of the creator is to sort out all the stuff you're not going to use. It's a process of filtering all these sounds in the world and saying, 'Gee, I wonder which sounds I'm going to work with and what story do I want to tell with them.' It might be mod-seven with diatonic scales or mod-11 with chromatic scales. I'm waiting for Peter to send me the data because, of course, they have to take that data from the seismometers, put that in the aggregate and crunch it."

With the world as an infinite source of sound — both musical and mathematical, composers like McClure have no shortage of places to explore.

"I'm just really excited about becoming a larger part of this world that puts musicians and scientists back together again."