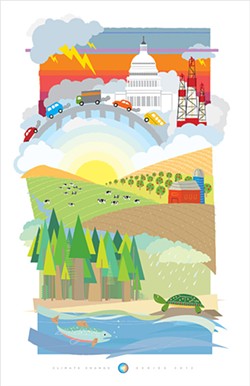

When it comes to climate change and public policy, three areas are virtually inseparable: the economy, energy, and politics. Often, the mix is not productive.

Climate is a system, and like any system one small alteration can mean larger changes down the line. Even small increases in average temperature can result in changes to things like precipitation patterns, which in turn can have economic effects.

Researchers are noticing long-term shifts in weather patterns, and they project that extreme weather — powerful storms, downpours, short-term drought — will occur more often. Each year, the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere increases. And global temperatures are averaging about 1 degree Fahrenheit higher than the historical baseline.

- PHOTO BY MIKE HANLON

- The United States needs to transition away from fossil fuels and toward renewables, says Linda Isaacson Fedele, chair of the Sierra Club's Rochester chapter.

Despite all this, a comprehensive national climate change policy remains absent.

"I think the main thing that needs to be addressed is that we really need to transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy as quickly as possible," says Linda Isaacson Fedele, chair of the Sierra Club's Rochester chapter.

The last attempt to get a climate bill through Congress was in 2008 and 2009. The legislation was a priority of President Barack Obama, yet Congressional Democratic leaders couldn't even solidify support within the party. Among the obstacles were coal-state representatives and senators who echoed the fossil fuel industry's argument that limiting emissions would be too costly. The cap and trade bill, as it was commonly known, died after a long slog, at a point where it had been picked apart and watered down.

Emissions growth and long-term changes in climate have costs and consequences. New York's dairy industry, which is poised for growth due to a boom in yogurt factories, offers one example. Cows produce less milk when it's hot, and a changing climate could mean more heat waves. A climate study released last year by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority said that, as early as next decade, dairy farmers could suffer heat-related losses of approximately $20 million a year. But the losses could be blunted if farmers take steps to adapt, such as installing cooling systems in their barns.

Absent federal action, nine Northeastern and New England states banded together to form the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative. The program puts a regional cap on carbon emissions from power plants and creates an emissions allowance trading system. The program is stabilizing and will ultimately reduce carbon emissions.

"It was set up to show the federal government that this could be done, and as sort of a prelude to federal action," which never happened, says Dan Hendrick, spokesperson for the New York League of Conservation Voters.

The current decade has seen a rapid uptick in severe and unusual weather. Before 2012, who really knew what a derecho was? For the record, it's a line of strong, fast-moving thunderstorms and this summer, East Coast states experienced several. In the Midwest, corn crops were scorched under a prolonged heat wave and drought. And in the West, which suffered the same hot, dry conditions as the Midwest, wildfires burned more acres of land than any other year on record.

That's just one year's worth of weather. Increasingly, climate-related disasters and challenges will require lawmakers' attention. If lawmakers don't develop comprehensive plans, they'll have to react event by event. And that leaves unaddressed the underlying cause: the large amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases generated by human activities.

Cheap fossil fuels are a big part of the energy-climate problem in the US and globally. Power plants run on them, they fuel automobiles, and certain industries rely on them, either as fuels or as product ingredients.

Coal, natural gas, and petroleum have a cost advantage because industry grew up around them, says the Sierra Club's Isaacson Fedele. To counter that advantage, the country needs to build-up infrastructure for renewables, she says.

The country's dependence on fossil fuels is driving the boom in natural gas extraction from deep shale formations. The energy companies knew about natural gas reservoirs in shale formations for decades, but accessing the gas was cost prohibitive. But prices for natural gas have increased, making the extraction more cost-effective.

- FILE PHOTO

- Fracking opponents marched on Washington, D.C. in July.

Shale drilling companies use a controversial technique to get the gas: high-volume hydraulic fracturing. Millions of gallons of fluid are blasted down a deep well bore at high pressures, which breaks apart the rock and frees the gas. Many people are worried about the health and environmental implications of fracking, particularly its potential to contaminate water supplies.

Yet federal and state governments have been slow to regulate or restrict fracking, and money and industry influence may play a role. Last year, the good-government group Common Cause issued several reports illustrating the flow of fracking industry money in Congress and state legislatures.

In one report, Common Cause said that "a faction of the natural gas industry" spent $747 million over 10 years on lobbying and political contributions. From 2001 through June 2011, the industry spent $726 million on lobbying and, through staff and political committees, gave $20.5 million to Congress members.

In another report, Common Cause New York — the statewide chapter — said that the gas industry spent $1.6 million lobbying New York lawmakers in 2010. State officials are conducting a lengthy environmental review of high-volume fracking in shale formations, and meanwhile, fracking is on hold. But over the summer, the New York Times reported that the Cuomo administration is considering a plan to allow fracking in some Southern Tier counties, as long as the affected communities approved the drilling.

Republican and Democratic elected officials — including President Barack Obama — have expressed support for increased natural gas drilling. Many see natural gas as a preferable alternative to coal, since burning it causes fewer objectionable emissions.

But a 2010 study by Cornell University Professor Robert Howarth said that natural gas extracted through fracking is not much better from a climate perspective than coal. The reasons: fossil fuels are used in the drilling process and to transport the gas, and methane could potentially leak from wells and pipelines.

Companies and politicians fighting against carbon regulations often invoke the cost of complying and the potential for higher energy costs. And many display and promote skepticism of man-made climate change, if not flat-out denial.

There may be costs associated with cutting fossil fuel emissions, but that's not entirely undesirable. Approaches like a cap and trade program or a simple carbon tax are meant to put a price on the carbon dioxide spewed into the air. The idea is to create a disincentive to pollute. And proceeds from something like a tax can be reinvested into efficiency efforts, technology development, and consumer energy bill assistance.

Climate change has costs of its own, across many economic areas. Farmers could see crop threats from new insect pests. And local governments may have to upgrade stormwater systems to cope with heavier, more frequent downpours, to cite two examples.

The NYSERDA report says that the potential for more frequent, more intense heat waves could increase summertime peak power demands — more people may turn to air conditioning to cope. Demand spikes could also mean spikes in the price of electricity. (As far as power infrastructure goes, the effect of long-term weather trends on electricity demand is just one of many factors, including industry and population shifts, that energy companies consider when planning infrastructure investments.)

How the federal government responds to climate change issues will depend in part on who's in the White House. Democratic President Barack Obama and his Republican challenger Mitt Romney have substantially different attitudes about climate change.

Consider the candidates' acceptance speeches at their respective conventions. Both backed a mix of fossil fuels, nuclear power, and renewables to meet the country's energy needs, though Obama emphasized investment in renewables.

During his convention speech, Obama touted new vehicle fuel-efficiency standards, which will lower vehicle-related carbon dioxide emissions. And the Environmental Protection Agency, during Obama's administration, issued rules to limit carbon dioxide emissions from new power plants.

Romney cynically dismissed Obama's push to lower carbon emissions.

"President Obama promised to begin to slow the rise of the oceans and heal the planet," Romney said, according to NPR's transcript of the speech. "My promise is to help you and your family."

The House and Senate have a role to play, too. But a polarized Congress may have trouble establishing federal policies to address climate-related disasters. Current debate over a five-year farm bill, which includes funding for drought- and disaster-relief programs, illustrates that potential.

The Senate passed a five-year bill, but the House version is stalled. Speaker John Boehner, a Republican, has said he won't bring the $900 billion bill to a vote until after the November election.

But last week, The Hill newspaper reported that a bipartisan coalition of House members from "farm-heavy districts" is trying to force a vote. Grassroots advocacy on specific issues, including putting local pressure on lawmakers, may ultimately be the best way to advance policies that address climate change or aspects of it, Hendrick says.

"It really helps to frame it in different terms instead of vague climate change," Hendrick says.