African-American artists, like women artists or gay artists, often find themselves in the dubious position of representing a group with their work, whether or not it is their intent to do so. For the current exhibit up at Nazareth College Arts Center Gallery, curator Deborah Ronnen wanted to provide a look at what African-American artists are doing in the printmaking process today, and was interested in including artists who address their ethnicity in their work. The resulting exhibit includes 13 artists, represents a wide variety of printmaking techniques, and provides a sensitive and nuanced look at a very complicated identity.

We don't often consider it this way, but the term "African-American" groups a diverse set of people based on outward appearances, and perhaps united foremost by their shared fates of stolen legacies and the ongoing denial of an equal standing in the present. The works in the show reflect on family histories, on self-generated futures, and on inner worlds shared with ambassador audiences.

Ronnen has included work by three winners of MacArthur Foundation "Genius" grants, including Martin Puryear's understated "Black Cart," which greatly resembles his sculptures in simplicity of form, complexity of subject, and that tar-black coating that casts a shadow on certainty.

The exhibit presents a spectrum of the ways artists treat contemporary black identity, whether it's telling their histories, reclaiming histories in which they were left out, or reinventing reality from very inspired scratch. For example, the show includes two of Radcliffe Bailey's collages based around tintypes of women in Victorian garb from family albums. For Bailey, race and pride in personal ancestry are the direct and central message.

Similarly, the nearby prints by Mickalene Thomas, who currently has an exhibit at Brooklyn Museum, depict beautiful, confident, powerful black women, including first lady "Michelle O." In "Why Can't We All Just Sit Down and Talk It Over," a regal woman lounges with one breast bared, confronting the viewer with the titular question.

Kerry James Marshall was trained in classical art history and technique, says Ronnen, but he found a lack of black representation (or a wealth of misrepresentation) in the cannon or western art. His etchings are created after traditional styles: in particular "Untitled (Handsome Man)" is a work akin to Rembrandt's portraits of grandeur, dignity, and stillness of gaze. Marshall is "referencing major artist printmakers," says Ronnen, "but he's made the subjects in his own image."

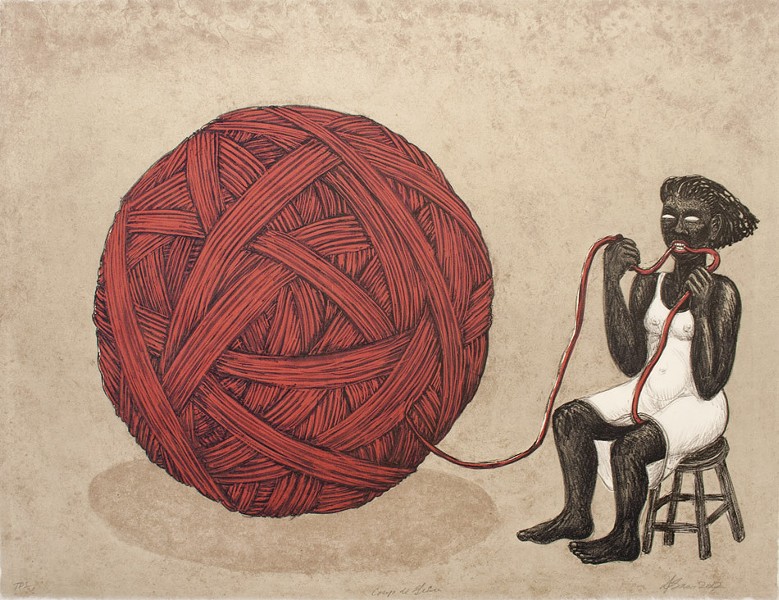

Like Puryear and some other artists in the show, Alison Saar isn't known first and foremost for her work in printmaking. The sculptor will frequently create post-sculptural studies of her 3D works, which is not common, but allows her to further meditate on the concepts she's working with. For example, Saar's work "Inheritance" is after a sculptural work by the same title, with very similar imagery of a young Atlas-esque figure standing with a massive cloth bundle on her head.

The work, as with others in the show, alludes to Saar's mother, who had to shoulder the weight of her household at a tender age. Different effects are expressed in the different dimensional versions of the work. While in the print, the figure stands in the heavy shadow of the bundle, in the sculpture, the weight and bulk of the bundle are more evident, says Ronnen.

The show also crucially tackles the persistent "us vs. them" race-relations questions that plague our culture. The works of Dread Scott — an artist who took his name from the subject of the iconic Supreme Court case that failed to "grant" citizenship to black people — silently ask us to consider the inequity involved in reaping the rewards of labor. Superimposed over a smiling Hattie McDaniel (the first African-American to receive an Academy Award, but for playing the role of a caricature servant in "Gone With the Wind") is text that asks, "If white people didn't invent the air, what would we breathe?" This piece is flanked by two nearly identical works that ask why it is that "we" feel threatened by "them" and vice versa. Despite the stark, pointed nature of these works, there are slow, unfolding elements involved in which viewers realize they are being confronted by two sets of huge eyes in black-on-gray ink, and also that the viewer is mirrored in the dark space of the image.

Equally challenging is the rarely-shown-together suite of four prints by Kara Walker, who is best known for her black silhouette work which, like the prints here, are emotionally charged with racial and sexual tension. I was most struck by the print "Cotton," in which a black woman is depicted tumbling into a vat of downy, oversized cotton blossoms, revealing what a master the artist is at created loaded, dichotomous imagery.

Trenton Doyle's florescent, screen-printed wallpaper and colorful etchings depict a terrifying self-created mythic saga, complete with an epic battle between the Mounds and the Vegans, an allegory with an eventual outcome of subduing the oppressor and making them see beyond black and white.

Similarly, the Artists of Gee's Bend have pieced together their own world from scraps. The story of several women, all descended from slaves, who like their mothers and grandmothers create vibrant, unique quilts from scraps of garments, is told through video, personal statements, and unique etchings made collaboratively by the women and master printers, originally for a show at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Several of the prints are in this show, resembling improvised flags from made-up nations, each stitch, texture, and fold of fabric preserved through the unique process of pressing the quilts into copper plates treated with beeswax. Learning the moving history behind these accidental art objects is definitely worth spending time with this segment of the exhibit.

Perhaps the most understated and yet brilliantly effective work in the show is by young artist Jennie C. Jones, whose "The Components" suite is made up of three tall, narrow, minimalist screen prints. A central image of silver, overlapping strings on white is flanked by what appear to be two black rectangles with hints of hot color. Jones's aim is to connect the often-overlooked contributions of African-American musicians to minimal work, and her work certainly awards intrepid viewers. A quick glance at the prints suggests flat, black, simple subjects, but those who approach and spend a little time sink into the depth of a shimmering, surprise starfield, glimpse the universe, and detect the fullness. The strings of the center work reveal countless, impossibly tiny hatchmarks, come alive in the imagination with vibrating bass beats. Jones's minimal art, like someone who is a stranger to us, is deceptively complex, and poetically chides us for dismissing what we can only see fully with intent and focus.

"Coup de Grâce" by Alison Saar is included in the "Contemporary African American Printmakers" exhibit currently at Nazreth College. PHOTO PROVIDED