It's such a loaded term. Our first reaction is that it's just a sad case of internal racism, black kids being peer-pressured into performing badly in school. But, like most issues involving race or class, it's more complicated than that.

University of Rochester Professor Signithia Fordham, who has spent a portion of her academic career observing the "burden of 'acting white'," does not want us to blame the kids. Instead, she wants us to see the trap African American kids --- both the ones being taunted and the ones doing the taunting --- are in.

Yes, the idea of "acting white" stems from racism. But Fordham says we have to pay attention to where the racism is coming from. Blaming black students for the black-white achievement gap, she says, is like blaming blacks for being forced to sit at the back of the bus.

If anything, the notion of "acting white" is gaining in popularity ("I feel like it's back to the future," Fordham says). So 20 years after her initial essay on the topic, we've invited Fordham, along with one of her students, to write about it.

Professor and student, obviously, see the problem from two different perspectives, two different stages in life. But they overlap in their discussions of identity, of race, of success --- and of the uphill fight many African American students still face.

Back to the future

by Ron Netsky

Congressman BarackObama spoke about it in his keynote speech at the Democratic Convention in 2004. New York Times Columnist John Tierney wrote about it last November. Harvard economist Roland G. Fryer did an exhaustive numerical analysis of it. And last week Claude Lewis invoked it in the Philadelphia Inquirer (in a column reprinted in the Democrat & Chronicle).

Since its popularization in a study by anthropologists Signithia Fordham and John Ogbu in the Urban Review two decades ago, intellectuals can't stop talking about the stigma attached to black students perceived to be "acting white."

Fordham, Susan B. Anthony Professor of Gender and Women's Studies at the University of Rochester, wrote a book, Blacked Out: Dilemmas of Race, Identity and Success at Capital High (University of Chicago Press, 1996). In it she explored "acting white" and other issues based on her 1981 to 1984 study of a predominantly black Washington, D.C. high school.

Fordham herself had been accused of "acting white" during her high school years, but at the time she blamed herself for perhaps being too outspoken. When she first encountered the phenomenon at "Capital High" (a pseudonym for an actual school), she was in denial about it.

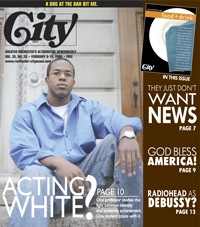

- Gary Ventura

- Its about how we change the social system. Professor Signithia Fordham.

A highly regarded scholar, Fordham has published numerous articles involving race, gender, identity, and education. But it is her concept of "acting white" that continues to generate debate.

In a recent interview Fordham discussed "acting white" and related issues. The following is an edited version of our conversation.

City: Claude Lewis recently wrote, "Every black parent ought to be outraged at youngsters who believe that those who seek education are 'acting white'..." He is the latest to misunderstand your concept.

Fordham: It's misunderstood far more than it's understood. First, people limit it to the school context. Then they create a false dichotomy, kids who are seeking academic achievement and kids who are not. That is a component of "acting white," but "acting white" is much larger than that. It's part of the larger African American community. That's why I wrote about Rosa Parks. "Acting white" not only means conformity, it is also resisting prevailing norms and expectation. It's not just school.

City: But when people like BarackObama use the term, they see it simply as a stigma that keeps black kids from achieving.

Fordham: When I think about "acting white," I think about black people trying to avoid or erase humiliation, because I see humiliation as the primary issue that affects people who are stigmatized.

City: You suggest that inferior schooling, lack of job opportunities and other social conditions have caused blacks to feel inferior and to ascribe academic achievement to whites. What's your reaction to people like Bill Cosby who put the blame on blacks themselves?

Fordham: It is truly unfortunate that he thinks the interactions of the people on the back of the bus make them responsible for their consignment to the undesired seats. As you know, even if they behave like saints, they do not have the power to change the seat assignments. Someone else must do that.

Look, I know it isn't popular these days to talk about enslavement, to talk about humiliation, to talk about identities as enclosed, because everybody's now saying everything is so porous you can get through these things and it's not the situation. But I'm devastated when I read things like what Bill Cosby said about this, because I think that doesn't capture what the issues are.

It's as if the black people on the bus were responsible for the fact that they had to sit at the back. That's not true. Rosa Parks was compelled to sit in the seats she was assigned, not because black people said she should sit there. She was assigned to those seats because that's where society said she should sit.

So it's not about black people against other black people, it's about how we change the social system so that all black people will benefit.

City: In "Blacked Out," you write that one of the things that seems to make the education process difficult is generational.

Fordham: After the Brown decision and the Civil Rights act --- in the 1960s generally --- black people were engrossed in acknowledging what they had achieved. Their children were the kids that I studied, and their parents were always baffled by why their kids wouldn't take advantage of what they saw as the wider opportunities available to them. And rightfully so. You fight for something so hard, why don't the kids do so much better? Because if we had those opportunities, we would have gone much further in life than we've actually gone.

But they don't get what is happening in culture systems, how they operate. These kids are fearful of the loss of identity. This is not something they would verbalize or even have the understanding to talk about if you asked them.

City: How do you feel about so-called Black English? Will students who use Black English be at a disadvantage?

Fordham: It's a very powerful issue that people seek to avoid, but I think black kids are extremely victimized by it, by the schools' stigmatization or humiliation. The language that people use --- you can't disregard that. Language is a critical component of culture, and what the school says is that you have to divest yourself of the language that you learned at your mother's breast. So kids stop engaging, stop talking, stop participating.

There are so many ways you can get kids involved if you accept them for who they are. Identity is very important in what kids do. Some things you don't do because it's not part of your identity and it's a violation. In some ways, people who are black and "acting white" are violating what is seen as a black identity. And that's what's missing in the analysis of "acting white."

City: But ultimately, doesn't a person have to learn to speak standard English to succeed in society?

Fordham: To be perceived as an intellectually smart person, yes, they have to learn to speak standard English. That's important. But I can think of so many people who make millions of dollars in America who can't put a sentence together in the way intellectuals think they should. To say that Black English is the reason kids are not getting through school or not doing well as adults is not the whole picture.

City: How do we get kids --- not just black kids --- to value education?

Fordham: If education is rewarded, it will be valued. If it's valuable to be a football player, kids will gravitate towards that. If we value education, we'll reward kids for getting that. If we value teaching, we'll reward people for teaching. But we don't.

Was Rosa Parks 'acting white'?

by Signithia Fordham, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Susan B. Anthony Professor of Gender and Women's Studies, University of Rochester

Was Rosa Parks guilty of "acting white" that day in Montgomery when she refused to give up her seat to a white man who boarded the bus? When the other black passengers did not initially support her because she was upsetting the imposed and customary order of race relations and they feared white reprisals against the whole black community, were they responsible for the insult to her dignity?

Mrs. Parks's defiant refusal to continue to accept the socially and legally mandated dehumanization of black people in Montgomery led her to act as if she were entitled to first-class American citizenship, with all the rights and responsibilities that implies. Her decision to remain seated when she was expected to stand up triggered a cascade of collective, public acts of resistance to segregation, securing access to public transportation, desegregated schooling, and the vote for a host of minority groups.

In the wake of Mrs. Parks's recent death and a conference held jointly at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University called "Acting White" Revisiting Ogbu and Fordham's [sic] Hypothesis (on October 28 and 29, 2005), I am reminded of the controversy that followed the publication of my article with John U. Ogbu, "Black Students' Schools Success: Coping With the 'Burden of Acting White'" (published in The Urban Review in 1986).

In my anthropological study of academically successful students at overwhelmingly black "Capital High" in Washington, D.C., I found that all black students were alienated by the mismatch between the culture of their community and that of the school. Some resisted by refusing to comply with assignments, while others resisted by defying their teachers' low expectations and becoming academically successful.

Virtually all black students paid a price: some by dead-end educational and occupational careers, and others by "acting white" and losing their own voices.

The conference planners misinterpreted my argument and, like so many others had done before, limited "acting white" to valuing or devaluing schooling. While my research was centered in a high school, its scope was much larger. Following traditional anthropological research practices, I treated the school as the "village" center and presented a wide-ranging analysis of the cultural practices of the group. For African American youth, "acting white" was associated with what was historically thought to be the prerogative of white Americans. Schooling was only one of those prerogatives; access to stable, well-paying jobs was another.

In a situation in which these formerly "white" prerogatives are simultaneously made available and denied, black youth responded with uncertainty and ambivalence, and, in some instances, a collective oppositional black identity emerged. Because a black identity is at the core of the response to the accusation of "acting white," I cannot embrace the idea supported by recent researchers, including the conference planners, that all high-achieving students --- regardless of race or class --- are stigmatized and subject to ridicule and exclusion by their lower-achieving peers. I resoundingly reject their conclusion that the problem of "acting white" is "not a black thing." This misinterpretation of pervasive patterns of inequality in American high schools is hauntingly familiar.

My research findings were initially distorted to hold the less academically successful peers of the high-achieving black students I studied responsible for the underachievement of all African American students. These alienated, envious, and unsuccessful students criticized their peers for "acting white." But they were not responsible for the black-white achievement divide. That is not what I said, and it is not what I meant.

A similar distortion emerged at the recent Acting White conference. The presenters suggested that the source of the problem is not unequal structure of the system of schooling in America and that the problem of "acting white" does not exist. A handful of African American high school students enrolled in elite classes in the "Research Triangle" area were paraded on stage and asked to report whether their black peers accused them of "acting white." Not surprisingly, following the pattern reported in the researchers' recent article, these academically successful black students said "no," and their verbal denials were used as empirical evidence that this phenomenon does notexist in most schools and could not impede the academic achievement of contemporary African American students.

Most reasonable people would agree that, like the black people on the bus with Mrs. Parks that day, the less successful black students are not the major obstacles to the elimination of the black-white achievement gap. Like every black person on the bus that day, all African American students are victimized --- regardless of their academic performance --- by social policies and educational practices that challenge their humanity and aspirations.

How ironic that in the current debate about the black-white academic achievement gap, we overemphasize the influence of students who are not doing well academically on the performance of black students who are successful. At the same time, we fail to examine the configuration of power on the bus and underemphasize the power of the social configuration of the school, especially racialized academic tracking and teachers' low expectations of black students' academic performance.

Twenty years ago, I concluded that academically successful students at Capital High were compelled to "cope with the burden of 'acting white'." After reviewing what has been written about the schools that most American students of African ancestry attend today, I am convinced that my earlier research was not seriously flawed and that the notion of "acting white" is still very much "a black thing."

- Gary Ventura

- I wasnt yet aware that I even had to compete. Nathan Gibbons.

'Stop acting white'

by Nathan Gibbons

The following is compiled from two essays written for one of Professor Fordham's classes, in 2005.

Identity is by no means static; it is an ever-changing facet of every individual's social being. Not all identities are self-made; they are often imposed as a result of social construct. I've found that a person's identity may change, to some extent, based on how that person conforms to certain social expectations.

Social positioning, for example, has succeeded in impressing certain identities upon the social groups to which it is associated. While growing up, I wasn't as aware of some of these social structures. This is partly because I didn't conform to many of the expectations that come with being a black person.

While the other black kids were loud and got into trouble all the time --- a sort of in-your-face resistance aimed at the social elite --- I was that kid that apparently acted like something I wasn't. "Stop acting white" is what the other black kids, including my brothers and sister, said about me with alarming frequency.

While the other blacks used "loudness" to affirm the worth of their existence, I resisted in a more subtle manner. I resisted society's preconceived notion that black kids would never amount to anything. I did this by positioning myself right smack in the middle of the social elite. I convinced myself that in order to thrive, I had to find a way to become popular, which then meant being rich and white.

After failing to do this several times, I soon discovered a loophole that would allow me to penetrate the seemingly insurmountable wall that separated me from the social elite. Through sports, I went from non-existent to well known and even to admired by those who would ensure the place I felt I was entitled to in high society.

Despite the relief and contentment I felt upon finally being accepted by the rich white kids, I experienced an unmistakable contrast of identity roles. It seemed that the more I fit in with the "pretty boys," the more I was ridiculed by the groups to which I inherently belonged. I can actually remember circumstances in which I was torn between hanging out and affiliating myself with my family and being with my newfound but not so genuine friends. With a great deal of shame and embarrassment I admit that I often chose my friends.

Ironically, though there was a time when I would disregard the importance of my cultural roots, it was these same roots that instilled the resiliency and perseverance I showed in climbing the social ladder. My father taught me not to settle for the scraps that society can and often does try to give me, but also to never forget where I came from. Needless to say, this task was a little too difficult for me at the time.

The perception of what it is to "win" or "lose" varies between social groups. "Winning" to one individual or group can be "losing" to another. This certainly rings true for me. A black member of a predominately upper class white school environment, I was almost immediately faced with the question of which team I should compete for --- only I wasn't yet aware that I even had to compete.

While I was self-driven to do well in school, I had no idea that my academic success would warrant some backlash from those to whom I was culturally attached. I excelled in the classroom, dominated in sports, and even managed to work my way into a very socially prestigious network of friends, and was thus a self-made winner.

I enjoyed my upward social movement immensely --- so immensely, in fact, that I deliberately compromised the relationships between me and my siblings.

To them, the ends were in no way, shape, or form justified by the means.

To them, I had no concept whatsoever of the things in life that are truly important.

To them, I was a loser.

I was criticized for what I considered to be success. It wasn't unaccepting whites that ridiculed me, but those I inconsistently considered to be my own. In trying to gain standing with my friends, I became the focal point of scrutiny to other individuals, namely my own family.

When I look at the past and the extremes I went to in pursuit of social prominence, I experience an array of emotions. I am now a student in an elite institution, a student who's had tremendous academic and athletic success, and a student whose relationships and connections will undoubtedly continue to be very beneficial, as they already have.

With my coming of age, I've become more aware of the social structures that led me to feel inferior. I still feel horrible when I think of how I ignored the importance of the relationships with my brothers and sister. We are closer now than we've ever been, due in no small part to my maturation, but I can't help but wonder what my life would be like had I not chosen to, at least in some ways, abandon my culture for a more socially acceptable one.