One of the more unusual documentaries to appear in recent years, "Tim's Vermeer" demonstrates the continuing appeal of the nonfiction form even in this age of blockbusters, comic-book flicks, and computer-generated images. As the title indicates, the film deals with the great 17th Century Dutch artist Johannes Vermeer, the subject of the lovely 2003 picture, "The Girl with a Pearl Earring." This film examines the possible methods that enabled the artist to create his remarkable paintings, with their unique underlying brightness, their intense colors, and their extraordinary attention to detail, attempting to explain the qualities that distinguish his work from that of other artists of his time and place.

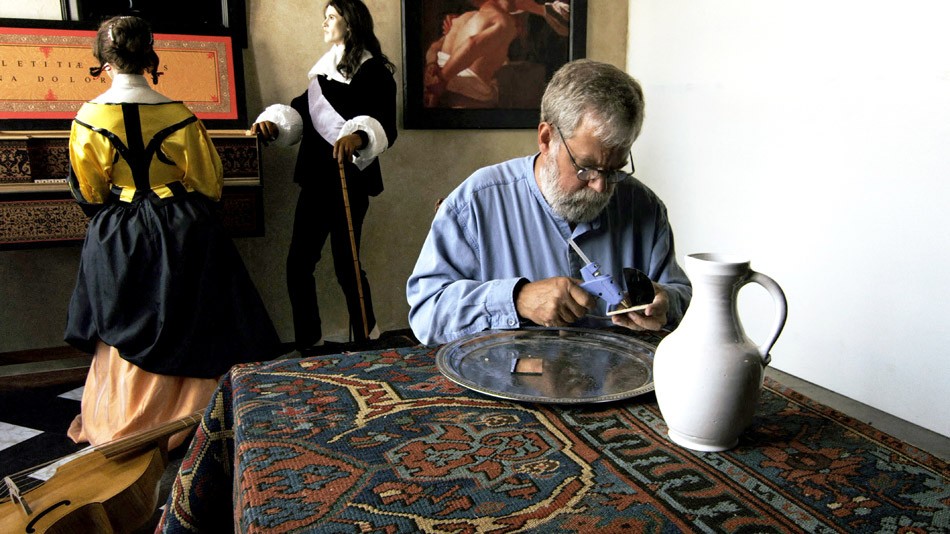

- Tim Jenison in "Tim's Vermeer."

Beginning with the people behind its production, the movie provides a number of surprises. Directed by Teller, the silent member of the brilliant magicians Penn and Teller, and narrated by Penn Jillette, a generally obnoxious blowhard, it introduces Tim Jenison, who announces to the camera that he is not an artist but nevertheless intends to paint a Vermeer -- a bold statement.

A wealthy and most successful inventor in the computer field, and an old friend of Jillette, Jenison bases his ambition on a book by the famous English artist David Hockney, who claims that Vermeer painted his pictures using the technology of his day, mostly in the form of the camera obscura. The film shows some of the history of that relatively simple device and Jenison's attempts to duplicate what he imagines were Vermeer's methods. His efforts turn into a demanding, fascinating, even obsessive labor of love, which provides the emotional subtext of the movie.

Jenison visits Holland to see the Vermeer museum, the house where he lived and painted, the landscapes of Delft and Amsterdam, and learns to read Dutch to study some of the works about the master. On a couple of occasions, he journeys to England to consult with Hockney and an Oxford scholar named Colin Blakemore, and even persuades the folks at Buckingham Palace to allow him to study an original Vermeer painting, now the property of Queen Elizabeth.

Back in San Antonio, Texas, where Jenison lives, he rents a warehouse with the proper northern exposure and, amazingly, sets about the construction of an exact duplicate of the room in the painting he proposes to copy, "The Music Lesson." He builds the furniture himself, purchases a viola da gamba and a virginal, the instruments in the painting, copies the windows, the ceiling beams, the floor tiles, enlists models to assume the positions of the young female pupil and her music teacher, assembling all the elements -- a stunning achievement in itself.

With everything in place, using the camera obscura and a mirror, he captures the images of the figures and objects reflected on his canvas, and in effect painstakingly fills them in with his authentic paints and brushes, a task that requires an exhausting amount of effort. The whole tedious project, carefully filmed through all its stages, takes more than five years from beginning to end; when he finishes, Jenison believes he has actually painted "The Music Lesson," and both Hockney and Blakemore concur.

"Tim's Vermeer" exploits one of the most successful and entertaining practices of American film, its ability to show process, the step-by-step actions of doing work and making something -- digging an irrigation ditch, tarring a road, erecting a barn, carving a baseball bat -- and endowing that activity with a fascination all its own. Jenison's remarkable journey through the many stages of his ambitious quest consists almost entirely of a series of carefully planned, artfully managed tasks, all of them terrifically cinematic. Beyond all that, Jenison himself serves as an appropriate hero of his own dream, an ordinary guy with enormous talent, pots of dough, and the willingness to pursue a quixotic adventure of the spirit.

The movie provides an engrossing lesson in history, art history, and art itself; like Hockney's book, its conclusions surely invite controversy and debate. Although nobody in the film wants, or perhaps bothers, to utter the point, Jenison's work and his conclusions may ultimately reduce -- if that's the right word -- Johannes Vermeer from a great artist to a great technologist, from an unusually accomplished painter to a remarkably skilled, patient, and meticulous draftsman.