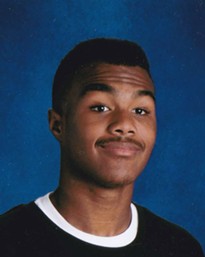

- PROVIDED PHOTO

- Chase Coleman

Instead Coleman had to have two discussions with him: one about his disability — Chase is one of the roughly 3.5 million people in the US who have autism — and the other about racism.

The first discussion came after a birthday party several years ago when a couple of children noticed that Chase needed help tying his shoes. After some children teased him, Chase told his mother he wanted to leave. That led to a conversation about how some people treat others, she said in a phone interview on Monday morning.

“’Do you know when someone is being nice to you, and do you know when someone is being mean to you?’” she asked. “And he knew the difference.”

The racism talk came only last month when Martin MacDonald of Pittsford admitted that he shoved Chase, 15, to the ground. The altercation took place in Cobbs Hill Park where Chase, who lives in Syracuse, was participating in a cross country race.

MacDonald, who is white, told police that Chase, who is nonverbal, was acting strange and appeared to be on drugs, according to reports. MacDonald, who has pleaded not guilty to second-degree harassment, said that his car was broken into by a black youth sometime prior to the incident, the Washington Post reported. He said he was afraid that Chase was going to steal his car.

What followed was a difficult conversation between Coleman and her son because about half of Chase’s aides and educators are white and some are extremely close to him. How do you explain that this was just one white man who behaved badly? Clarise Coleman said.

Another issue: Some of the behaviors that MacDonald attributed to Chase are consistent with autism spectrum disorder and are often misread.

“Kids with autism look like everybody else on the block,” says Laura Silverman, a child psychologist at the University of Rochester Medical Center. And often it’s not until a person tries to communicate with an individual with autism that the disorder becomes apparent.

The abilities of children on the autism spectrum vary widely from low functioning to college-level skills, Silverman says. But many have difficulty with social interaction, and their ability to communicate is sometimes limited to the literal, almost to the extreme, she says.

Many autistic children lack the back-and-forth responsiveness that’s typical of conversational speech. They tend to repeat words and behaviors instead, Silverman says.

Some children may get confused and their anxiety level rises in situations that alter from familiar routines, such as getting lost, says Shanna Jamanis and Dawn Vogler-Elias, co-directors of Nazareth College’s interdisciplinary program on autism.

These characteristics are often misinterpreted by people who have never interacted with someone who has autism.

Chase has gone from being a shy kid who would only eat about three or four types of food, and who was sensitive to crowds and smells, to a caring and social young man, Clarise Coleman said. She worried most that his special kindness would retreat after his experience at Cobbs Hill.

“That part of him I always want to stay,” she said. “I just don’t want him to hate.”