Main Street Arts' latest exhibit, "Re-emerging Artists," showcases the work of Robert Marx and John Greene, two late-career artists whose art continues to evolve and gain new audiences. Nearly 70 drawings, paintings, and sculptures fill both rooms of the gallery's first floor, as well as an additional space upstairs. The majority of the work is new and has not been seen outside of the respective artists' studios.

Both Marx and Greene have been making art since the 1950's, and to this day each maintains a devoted studio practice. Although Greene has been collecting Marx's work since the 50's, and the two became friends, this is the first time they've exhibited their art together.

Greene spent 30 years working on Wall Street, but during that time always maintained a studio in the West Village, where he would go after the market closed and work tirelessly on large canvases. Greene's work has been exhibited nationally and is included in many private collections. Today he works in his home studio in the Hudson River Valley.

The show includes encaustic paintings from several different bodies of Greene's work, and include ethereal landscapes and color fields as well as many box-shaped, dimensional works. These pieces are presented on pedestals or are mounted to the walls, jutting out into space as multi-sided meditations on space and time.

Greene's work is about process and discovery, with a heavy emphasis on experimenting with materials. In his statement, he conveys a fixation on paint: "the color, texture, the joy of putting it on and scraping it off," he says.

Each work is created with vibrant and muddy pigments suspended in translucent layers of wax on wood or metal surfaces, creating an illusion of depth. The surfaces have a soft, silky appearance, as fragile and imperfect as skin, and blooming here and there with unpredictable, shimmering patinas from lead and copper.

It's easy to lose yourself when gazing into Greene's large, shifting colorfields. And his soft landscapes, with blurred and undulating horizon lines and forms, seem to be spied from the window of car racing through rural roads at various hours. A series of small cube landscapes mounted on the wall give the illusion of entire worlds enclosed in a transparent box.

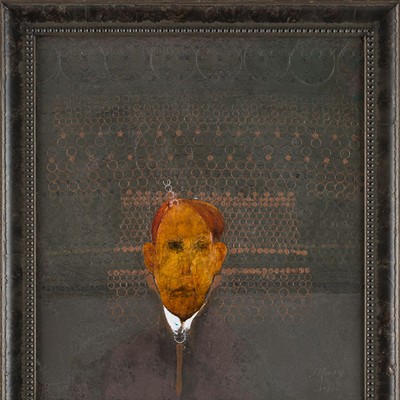

Marx's work has been shown internationally and is represented in major museum collections, including the Museum of Modern Art, The National Gallery of Art, and Whitney Museum of American Art. His highly developed style is recognizable as his own across various media. Here, oil paintings, works on paper, and bronze sculpture are each characterized by the presence of distorted, haunting figures.

"The people I draw, paint, and sculpt personify the human condition," Marx says in his artist statement. "They are also the people we see around us, every day."

Having witnessed certain patterns of this world's troubles in his lifetime, Marx's preoccupation with heavy aspects of human experience — the arrogance of power and the various ways its abuses manifest — show up in his work and weigh on his world-weary subjects.

Marx says he believes that we are "to some degree trapped by the conventions we have chosen to impose upon ourselves." Building on borrowed historic visual language, such as Picasso's use of dismembered bodies to convey futility, Marx pushes the point further with mannequins, masks, and dangling limbs pulled by puppet strings.

Low-relief texture covers all of Marx's work: the solid, cast-bronze heads have papery wrinkles around eyes and mouths and the faintest wisps of hair on the domes of heads; clusters of circles and scratchy lines crackle like frustrated energy surrounding his painted subjects.

Upstairs, a smaller gallery is filled with examples from a red-pencil drawing series Marx began as a daily drawing exercise last year, paired with a series of Greene's "Portal" paintings. At the center of each of Greene's paintings are windows into chaotic colorful worlds or voids energized with texture, with equally textured open space around them.

Like his other works, Marx's crimson drawings on off-white paper center on faces surrounded by clouds of energetic lines dispersing like smoke. They bring to mind Leonardo da Vinci's sketchbook studies of the human form, but while the Renaissance man was concerned with a perfect depiction of physical systems, Marx uses the body to convey emotional conditions.