Len Douangtavilay, a Level 3 sex offender, once lived 200 feet from athletic fields used by Penfield youth. The discovery of this fact has prompted Penfield officials to propose residency restrictions on sex offenders, potentially putting Penfield in conflict with state law.

New York's courts assign sex offenders a Level 1, 2, or 3 designation, based on the risk that they'll re-offend. Level 1 means a low risk, Level 2 is moderate, and Level 3 is high.

In 1998, a Utah court convicted Douangtavilay of a sex offense against a 14-year-old girl, prompting his Level 3 designation, according to the New York State sex offender registry.

Town officials say that they didn't understand at first why Douangtavilay was allowed to live so close to a park. They quickly learned that the only law governing sex offenders' residency is a state law that applies only to Level 2 and 3 offenders on parole or probation; they're prohibited from living within 1,000 feet of schools and day care facilities.

Douangtavilay wasn't on parole or probation when he moved to Penfield in January 2015. He was, however, facing a second sex-offense charge for allegedly raping a 13-year-old girl in 2004. The arrest warrant was issued by Seattle police in December 2014. (The state sex offender registry says that Douangtavilay currently lives at the Hotel Cadillac in Rochester.)

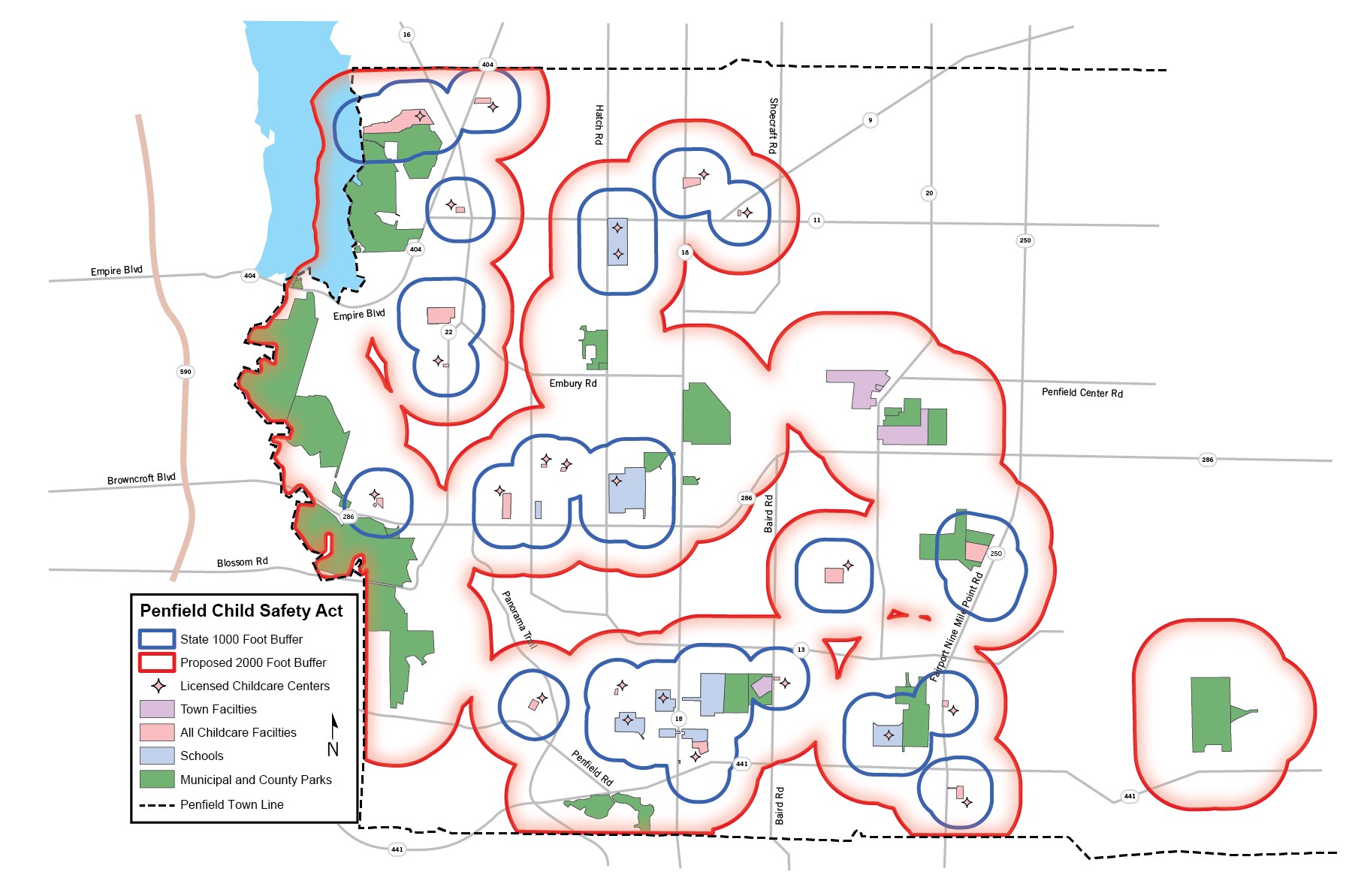

After finding out about Douangtavilay, Penfield officials proposed their own law, the Penfield Child Safety Act, and in doing so stepped into a statewide debate about how, and whether, local communities should restrict the residency of sex offenders.

- PHOTO PROVIDED

- Penfield Town Supervisor Tony LaFountain.

"We just did not believe that the state law went as far as it should," says Penfield Supervisor Tony LaFountain.

The proposed law, which was spearheaded by Town Board member Rob Quinn, would prohibit Level 2 and 3 sex offenders from living within 2,000 feet of schools, playgrounds, parks, town facilities, and licensed day care operations. It calls those areas "child safety zones," and offenders would effectively be barred from much of the town's built-up west side.

Sex offenders aren't popular neighbors, and they don't get much public or political sympathy (and generally for good reason). Approximately 130 New York counties and communities have passed laws that restrict, to some degree, where registered sex offenders can live — among them are the Town of Hamlin and the Village of East Rochester.

The laws are rooted in the belief that sex offenders are likely to re-offend: that they pose a danger to children and other vulnerable populations. And often, the laws are passed with broad public support.

But last month, the state Court of Appeals pushed the local laws into a legal no man's land. The court struck down Nassau County's sex offender residency limits and said that similar restrictions across New York are in conflict with state laws and are therefore, unenforceable.

Penfield's draft law, as well as a countywide measure proposed by Democratic County Legislator Justin Wilcox, is now on hold. Wilcox's legislation would prohibit Level 2 and 3 offenders from living within 1,000 feet of a school, preschool, or day care, or within 500 feet of a park.

The State Senate swiftly responded to the Court of Appeals decision with legislation, co-sponsored by Republican Senator Rich Funke, giving communities permission to set and enforce their own sex offender residency restrictions. The bill passed, with only four senators voting in opposition.

But the Assembly hasn't yet taken up the measure. The chair of the Assembly's Correction committee, Democrat Daniel O'Donnell, says that he'll hold a roundtable discussion in the spring to examine sex offender residency restrictions.

- PHOTO BY MARK CHAMBERLIN

- County Legislator Justin Wilcox.

Local restrictions do have critics, including some criminal justice researchers and the New York Civil Liberties Union. They raise crucial concerns about the wisdom, necessity, effectiveness, and fairness of the laws.

"The Court of Appeal's decision is not only the right legal decision, it increases public safety," said NYCLU Executive Director Donna Lieberman in a statement. "The current hodgepodge of competing and confusing local rules about where people registered for sex offenses can live and go fosters instability, gets in the way of treatment, and compromises public safety. A statewide, evidence-based approach that takes into account treatment and risk is the best way to protect communities."

The debate will surely intensify in the coming months as local communities try to figure out what to do with their laws and state legislators debate how to approach sex offender residency restrictions. As the issue churns, there's a danger that the debate could be driven by emotion and preconceived beliefs instead of objective analysis.

Three people spoke at a public hearing on Penfield's proposed law last week. All were in favor.

Greg Kamp, president of Penfield Little League, commended the board for the legislation. Each year, 1,100 Little Leaguers play on the baseball and softball diamonds at Veterans Memorial Park, he said, across from where Douangtavilay briefly lived.

"Their safety is of the utmost importance," Kamp said.

George Hebert, president of the Rochester District Youth Soccer League, said that he strongly supports the proposed law.

The most detailed comments came from Penfield resident Stefanie Szwejbka, a prevention education and outreach specialist with Bivona Child Advocacy Center. She began by reading a statement from Bivona Executive Director Mary Whittier which stressed education and awareness about ways to protect children and the warning signs of abuse.

Child sexual abuse is not easy to discuss, Szwejbka said, and people generally don't like to think or talk about it. So she said that she appreciates the town's public discussion of the issue.

"Open dialogue means that we can be vigilant not only in protecting kids in different ways, but also in maybe opening our minds up to being educated a little more about how we can protect kids, how can we talk to kids, what are some other things we can do to protect kids in addition to passing legislation," she said.

LaFountain made a similar point in an interview prior to the hearing. Even though town officials believe that sex offender residency restrictions are important to protect children, he said, the restrictions will only do so much.

"At the end of the day, I think we're only sticking our head in the sand if we don't admit the fact that as parents, counselors, guardians, grandparents, we've got a responsibility to watch after who's in our care." LaFountain said. "I don't care what laws you put on the books."

When Kelly Socia was a graduate student at the University at Albany, he studied sex offender residency restriction laws across Upstate, including their effect on sex crime rates and whether the restrictions could lead to a clustering of offenders.

The local laws are based on incorrect assumptions and haven't had a significant impact on sex crime rates against children, says Socia, now a criminal justice professor at University of Massachusetts-Lowell.

"Their goal obviously is to stop sex offenders from harming children, and they conceptualize this as sex offenders living near schools and day cares, meeting kids, and attacking them around these areas," Socia says. "Most of the sex crimes simply don't happen like that."

- Map by Matt DeTurck, with elements and data courtesy the Town of Penfield

In a 2008 journal article, Socia and two other researchers laid out their analysis of state sex offender arrest data from 1986 through 2006. And they found that in over 95 percent of the cases, it was the person's first sex offense arrest.

And often-cited research from the US Justice Department counters the whole idea of Stranger Danger. According to the DOJ, more than 90 percent of victims under 17 are assaulted by someone they know.

Socia and other critics of residency restrictions also point out that the local laws can push offenders from one community to another. Often, that means shifting offenders to poorer or rural neighborhoods.

The restrictions can make it difficult for offenders to live with or near family, often a vital support system for people just getting out of jail, Socia says. And if they're pushed out to rural areas, the offenders may also have a hard time finding housing, getting to jobs, or accessing treatment, he says. Family support, jobs, and treatment have all been shown to reduce recidivism, Socia says.

Some offenders may also stop registering — which is a crime — or become homeless, he says.

And increasingly restrictive residency laws can create other problems, too.

In 2007, Suffolk County passed a residency restriction law so strict that approximately 40 sex offenders on probation and parole — which means they aren't allowed to leave the county — were forced to live in two construction trailers, one of which was parked next to a prison. The county revamped the law in 2013, and the offenders were able to move out of the trailers.

County Legislator Wilcox says that his proposal is common-sense legislation. Many people believe that the law already prevents sex offenders from living near schools, parks, and day cares, he says.

He introduced the legislation shortly after a Level 3 sex offender, Justin Micciche, moved within a mile of a Webster school district high school and middle school. Students near the home typically walked to the schools, but the district began busing them as a result.

Wilcox takes issue with some of the concerns raised by critics of residency restrictions. His proposal wouldn't push offenders out of any community, he says. It would simply take the limits imposed by state laws, he says, and apply them to Level 2 and 3 offenders after their parole or probation periods are over.

And Wilcox says that certain subgroups of sex offenders are likely to reoffend, a fact that courts recognize through the risk designations.

For example, sex offenders with more than one conviction are more likely to commit new crimes, he says. And he references a 2001 report from the Department of Justice-backed Center for Sex Offender Management that says that offenders with a sexual interest in children are the most likely to reoffend.

But Wilcox also says that he doesn't want to just assume that residency restrictions work. He's also submitted companion legislation that would create a task force to study sex offender management in Monroe County.

The task force would examine the value of expanding residency restrictions, but also evaluate probation worker caseloads, how quickly Probation Department information on sex offenders can be shared with other law enforcement agencies, and the use of GPS monitoring for offenders.

Wilcox says that he'd like to see state lawmakers take a similar approach. While he says that he appreciates the intent of the State Senate legislation, and supports the ability of communities to set their own reasonable restrictions, it's important to look at what policies are actually effective.

"A law, if it just makes people feel better and it doesn't actually reduce the re-offense rate, then I would say we're not doing our job," Wilcox says.